Not to be confused with the Northern Railway of Canada

Introduction

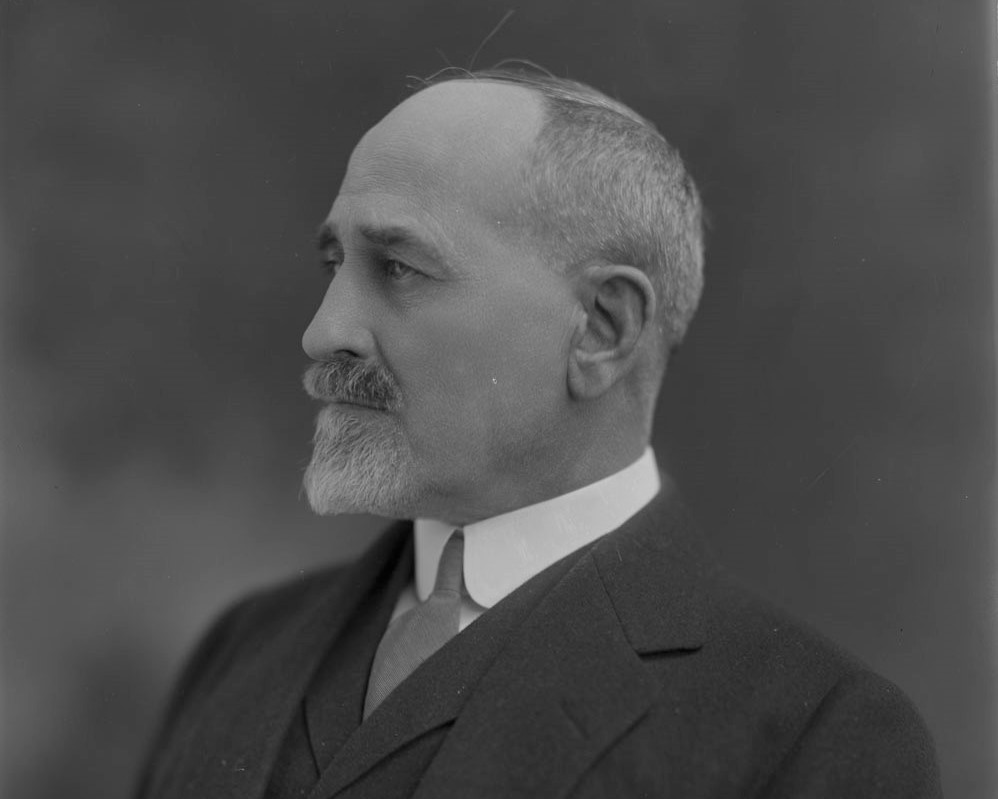

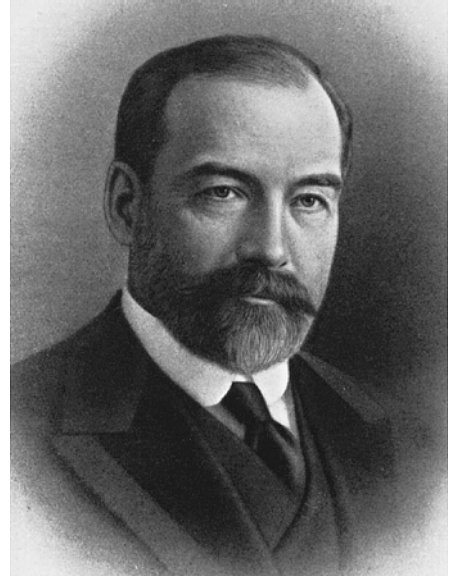

The Canadian Northern Railway was a late arrival to Toronto’s railway scene, as well as that of Canada in general. It easily made up for this through rapid and ceaseless expansion, becoming a transcontinental railway just over 15 years after its formation. It was somewhat unique compared to the other transcontinental railways in Canada, in that it originated as a relatively small enterprise in Manitoba as opposed to the larger Grand Trunk or Canadian Pacific undertakings further east. The pair of entrepreneurs behind it, William Mackenzie and Donald Mann, were knighted in 1911 for their achievements in the railway industry. Whilst their company only existed in the Toronto area for two decades, it would build up a modest network in the city and its environs to compete with the established Canadian Pacific and Grand Trunk Railway empires. Railway lines established by the Canadian Northern over a century ago still make up a significant portion of Canadian National’s system today, including some of its busiest corridors.

A Crisis in The Prairies

The story of the Canadian Northern Railway begins in Manitoba, where Canadian Pacific had established a portion of its transcontinental railway during the 1880’s whilst expanding westward. Specifically, it began with contention caused by clause 15 of Canadian Pacific’s charter, which states:

“For twenty years from the date hereof, no line of railway shall be authorized by the Dominion Parliament to be constructed South of the Canadian Pacific Railway, except such lines as shall run South-West or to the Westward of South West; nor to within fifteen miles of Latitude 49. And in the establishment of any new Province in the North West Territories, provision shall be made for continuing such prohibition after such establishment until the expiration of the same period”.

Colloquially known as the “monopoly clause”, this gave Canadian Pacific a stranglehold over much of central Canada by preventing the construction of competing lines across a very large distance, much to the ire of Manitoba’s provincial government. The lack of railway development permitted after the arrival of Canadian Pacific was not only stifling settlement in the province, but the CPR’s monopoly over rail service in the area allowed them to significantly inflate the price of transporting goods. The Manitoba government charged that since the province existed when the Canadian Pacific charter was written, the wording that limits railway development in “any new province” did not include Manitoba. Whether that was the case or not, in 1881 the provincial government began approving railway charters that could be considered in violation of the clause. Some of these railways were built to access the remote areas that Canadian Pacific had neglected, but others spread to Manitoba’s southern border where they could connect with Canadian Pacific’s major American competitors. Of course, this was a threat to Canadian Pacific and their control over the prairies.

The CPR made the federal government aware of what was going on in Manitoba. It was found that the offending charters were in violation of the Canadian Pacific charter, and as a result they would be vetoed in 1882. Public opinion towards the CPR in Manitoba plummeted for a number of reasons in subsequent years, not the least of which was an additional rate hike in 1884 and failing to construct its own branch lines in the province. The issue once again came to a head in 1887 when the province attempted to build the Red River Valley Railway to the southern border in spite of the federal ruling on the matter. The Red River Valley Act was disallowed by the federal government just as other railways before it, but this time construction would go on regardless. While construction of this railway was ongoing the following year, the Canadian Pacific had exhausted its efforts to acquire the Red River Valley Railway and would pursue more aggressive means. When the Red River Valley Railway attempted to cross the Canadian Pacific at grade, volunteer police would protect construction crews while they put a diamond crossing in place under the cover of night. It would be torn out by Canadian Pacific crews the next morning, eventually putting one of their locomotives in the way to block future attempts at completing the diamond. The “Battle of Fort Whyte” would occur on October 22nd, 1888, in which approximately 300 civilians supported by provincial police confronted the CPR workers. The confrontation was not necessarily a “battle” as one might imagine, though fistfights did occur between the two groups for several days. That winter, the Supreme Court ruled in favour of the competing railways in Manitoba effectively ending Canadian Pacific’s monopoly in the region.

Canadian Northern’s Manitoba Beginnings

With independent branch lines now authorized by the federal government, the Lake Manitoba Railway and Canal Company received a federal charter in 1889 to lay 27 kilometers of rail between Portage La Prairie and Lake Manitoba. The company was to then build canals between Lake Manitoba, Lake Winnipegosis, and the North Saskatchewan River for boat traffic. Shortly thereafter, it was determined that railways alone could more effectively facilitate transportation over that area and the charter was expanded to allow for 201 kilometers of rail between Portage La Prairie and Lake Winnipegosis. Construction of the railway stalled for several years afterward, and a wider slowdown of railway development in Manitoba prompted provincial cabinet member Clifford Sifton to introduce an initiative to guarantee company bonds issued for new railways within the province. It’s at this point that Sifton met Donald Mann, a railway contractor who had previously assisted with the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Now seeking work, Mann expressed interest in Sifton’s bond guarantee initiative. With the help of fellow contractor William Mackenzie, he would purchase the Lake Manitoba Railway charter for $38,000. Fred Nicholls served as president of the railway since Mackenzie and Mann couldn’t hold company director positions as contractors. The railway was finally opened to Winnipegosis in January 1897. In December of the following year, the Lake Manitoba Railway merged with the Winnipeg Great Northern Railway & Steamship Company under the name of the Canadian Northern Railway.

The newly formed Canadian Northern would begin ambitious plans to expand in all directions, acquiring a federal charter to do so in July 1899. Immediately thereafter, it acquired the Manitoba & South Eastern Railway which became the Canadian Northern’s first railway line into Ontario. The former Manitoba & Southeastern stretched southeast from Winnipeg, passing briefly through the U.S. state of Minnesota before reaching Rainy River, Ontario. Whilst branch lines were being established further west, eastward expansion would continue through a charter for the Ontario and Rainy River Railway. It was planned to extend from the Canadian Northern at Rainy River to the Great Lakes shipping hub of Port Arthur (now Thunder Bay), passing through many miles of the rugged and remote Canadian Shield. Construction was complete to Port Arthur on December 30th, 1901, directly competing with the Canadian Pacific whose transcontinental line already ran a more northerly route between Port Arthur and Winnipeg. The last spike of the O&RR was driven by Ontario’s Commissioner of Crown Lands Elihu Davis just east of Atikokan, Ontario. Shortly thereafter, the O&RR was fully absorbed into the Canadian Northern Railway. By 1902, the Canadian Northern’s lines already totalled an impressive 824 kilometers of track in operation with an additional 1,127 kilometers actively under construction.

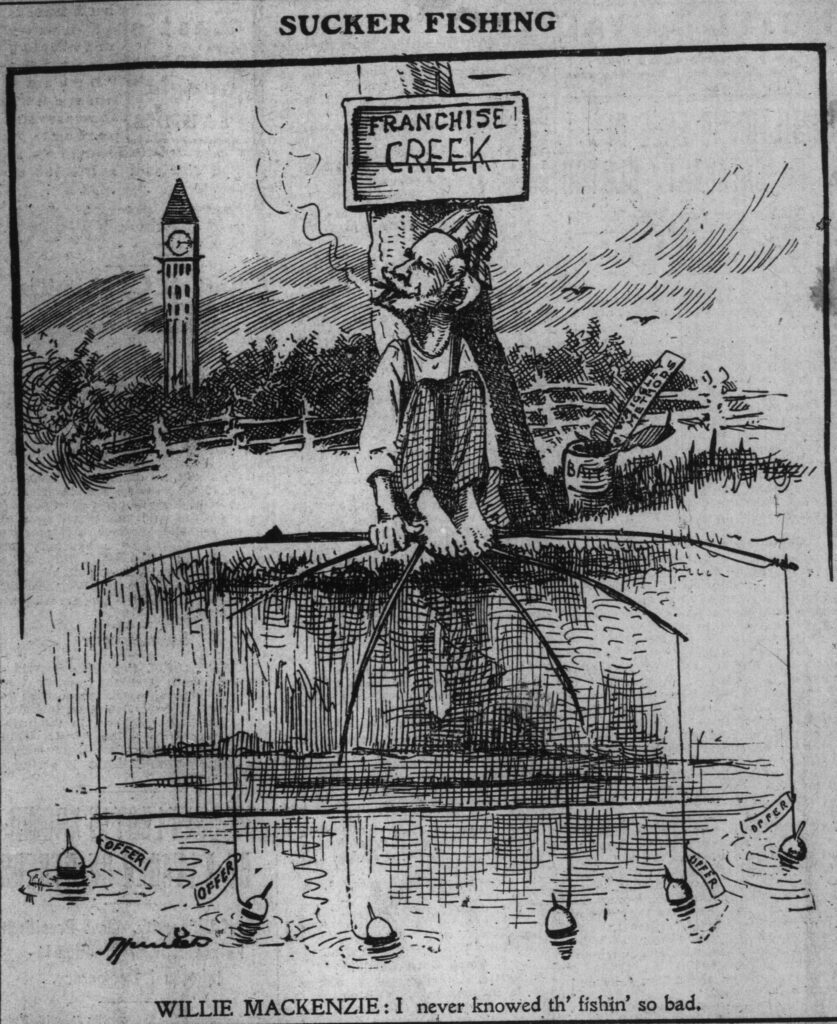

Mackenzie and Mann’s Designs on Toronto

Long before the broader Canadian Northern system was formed in the prairies, the duo behind it would quickly turn their attention to the eastern part of the country. William Mackenzie’s first foray with railways in Toronto occurred when the 30-year franchise of the Toronto Street Railway, a horse-drawn transportation system, expired in 1891. The City of Toronto granted another 30-year franchise to the Mackenzie-led Toronto Railway Company. Interestingly, Mackenzie’s investors included several prominent figures from the Canadian Pacific Railway, including James Ross and William Cornelius Van Horne. Under Mackenzie’s leadership, the horse-drawn system inherited from the Toronto Street Railway was converted to electric streetcars between 1892 and 1894. The Toronto Railway Company’s offices were located at the northwest corner of King and Church Street. Upon its formation, the top floor of the same building became occupied by the head offices of the Canadian Northern Railway. While it made sense for the national offices of this company to be located closer to the financial markets in Montreal, New York, and London, as well as the nation’s capital of Ottawa, in hindsight one could see how this might have been a sign of things to come for Toronto. The nearest segment of the Canadian Northern system at this point was over 2,400 kilometres (1,500 miles) away at the western end of the province, but this would soon change.

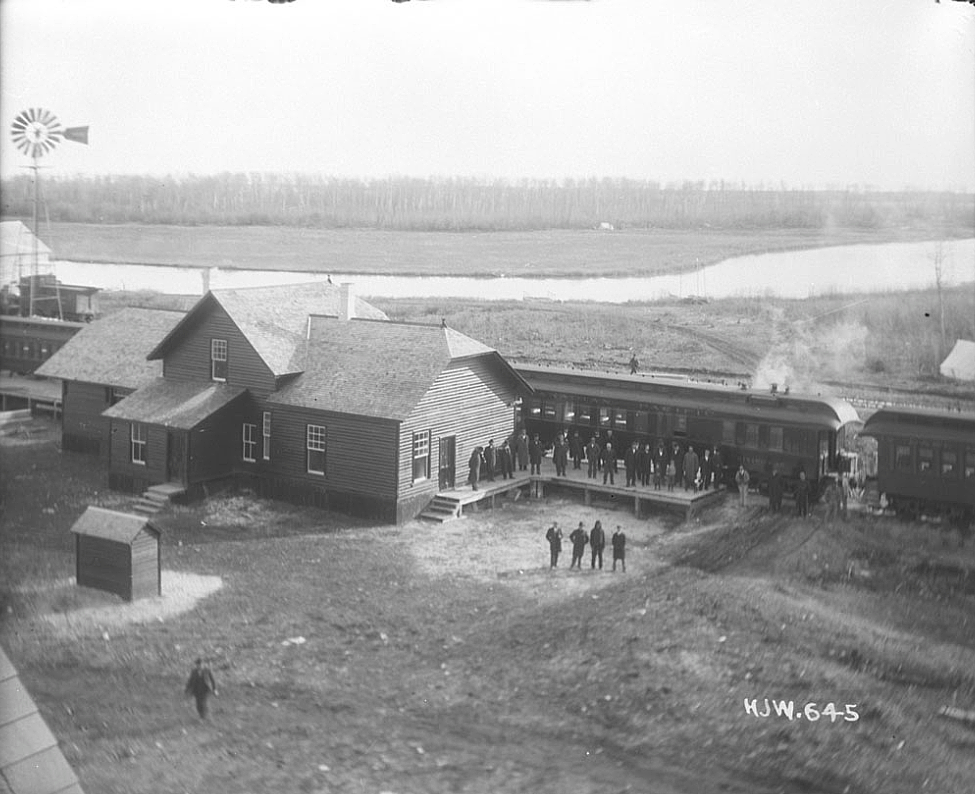

On July 22nd, 1895, four years before the formation of the Canadian Northern Railway, Mackenzie and Mann incorporated the James Bay Railway Company to construct a line between Toronto and James Bay. These plans changed multiple times early on, first by shortening its route to Lake Abitibi near Cochrane. By the time of the Canadian Northern Railway’s formation at the end of the decade, however, the James Bay Railway was quickly folded into Mackenzie and Mann’s broader plans for a transcontinental system. The first segment was constructed between Parry Sound and a place called Canada Atlantic Junction (now the small hamlet of Foley) on March 2nd, 1902, covering a distance of just under six kilometres (four miles). At the latter place it interchanged with the Canada Atlantic Railway, an independent venture that stretched from Depot Harbour to Ottawa at the time.

At the same time that the James Bay Railway had plans to extend south to Toronto, they would almost immediately face direct competition from the Canadian Pacific Railway. The latter had been trying to establish its own right-of-way between Toronto and Sudbury for decades. They had a tenuous agreement with the Grand Trunk Railway to bring Canadian Pacific traffic up to their transcontinental line in North Bay, but a passenger rate war resulted in the brief cancellation of this agreement. The only alternative for Canadian Pacific was an inconvenient jog east to Smiths Falls and Carleton Place for westbound traffic. The Grand Trunk’s attempt to establish its own transcontinental line in the early 1900’s was the final straw, and Canadian Pacific quickly began surveying its own route over much the same areas as the James Bay Railway. The two commenced construction around the same time, and the James Bay Railway took Canadian Pacific to the Supreme Court in an attempt to stop it. It was argued that Canadian Pacific’s charter did not allow for such a line and that they would require additional legislation. However, on April 6th, 1905, the Supreme Court ruled in favour of Canadian Pacific. The two railways would be built within as little as ten metres of each other in some places.

An even more bitter rivalry was only just beginning between the Mackenzie and Mann empire and the Grand Trunk. The Great Fire of 1904 burned a Toronto city block to the ground, and the City of Toronto was actively negotiating with the Grand Trunk and Canadian Pacific to use the site for a new Union Station. However, on July 4th, 1904, Toronto Mayor Thomas Urquhart announced to the Board of Control that the Canadian Northern Railway had just filed plans for their own passenger terminal on that site. This caused quite a stir among the controllers, and reportedly also became a topic of discussion on the streets throughout that afternoon. When asked whether he knew the site in question was already being considered for a new Union Station, Mackenzie replied that he “had not been aware that such an arrangement was under consideration”. While we can’t know for certain whether he knew, the interviewer seemed to interpret Mackenzie’s answers as tongue-in-cheek sarcasm:

“I don’t think there will be much change. We are on quite as good terms with the C.P.R. as the G.T.R.” replied the Canadian Northern president with a humorous twinkle in his eye. “We are all very good friends”.

The Toronto World, July 4th, 1904

Mackenzie seemed to be under the impression that a clause in the Railway Act would give his company the edge over the Grand Trunk in the application process. The opinion among the general public at the time was that the Canadian Northern had played a trump card. However, Mackenzie was ultimately proven wrong and it was the Grand Trunk who would have the upper hand. Their application for expropriation of the burned-out properties in Toronto was filed ahead of the Canadian Northern application to do the same by a matter of days. The land would end up in the Grand Trunk’s possession. This moment would set the tone for the rest of the Canadian Northern’s existence in Toronto. Perhaps more than anything else, they would be known for their bombastic, over-the-top proposals. Most of which would never come to fruition.

In August 1904, just a month before construction of the James Bay Railway began, the Grand Trunk would go on the offensive. They purchased the Canada Atlantic Railway outright, a move that came as a surprise to even Mackenzie and Mann. The duo were quite certain that they would be the ones to take over the Canada Atlantic, whose connection with Ottawa and prime wilderness for sportsmen and vacationers alike would have been valuable to the fledgling railway. An edition of the Toronto World from September 14th, 1904, summarizes the situation quite nicely:

“Mr. Mackenzie has evidently not yet accepted as final the Grand Trunk’s purchase of the C.A.R. He is at Ottawa now, in all probability, making his last appeal. If he is beaten a new situation will be created. He must either fight the C.P.R. and the Grand Trunk, or form an alliance with one of them. It may be that he will be driven to identify his interests with the C.P.R., either as a merger or a joint arrangement, probably the latter”.

While the author of this excerpt was referring to a joint CNoR-CPR arrangement over the entire James Bay Railway that would never occur, the quote will seem shockingly accurate when applied to the context of Toronto several years later, as we will soon learn.

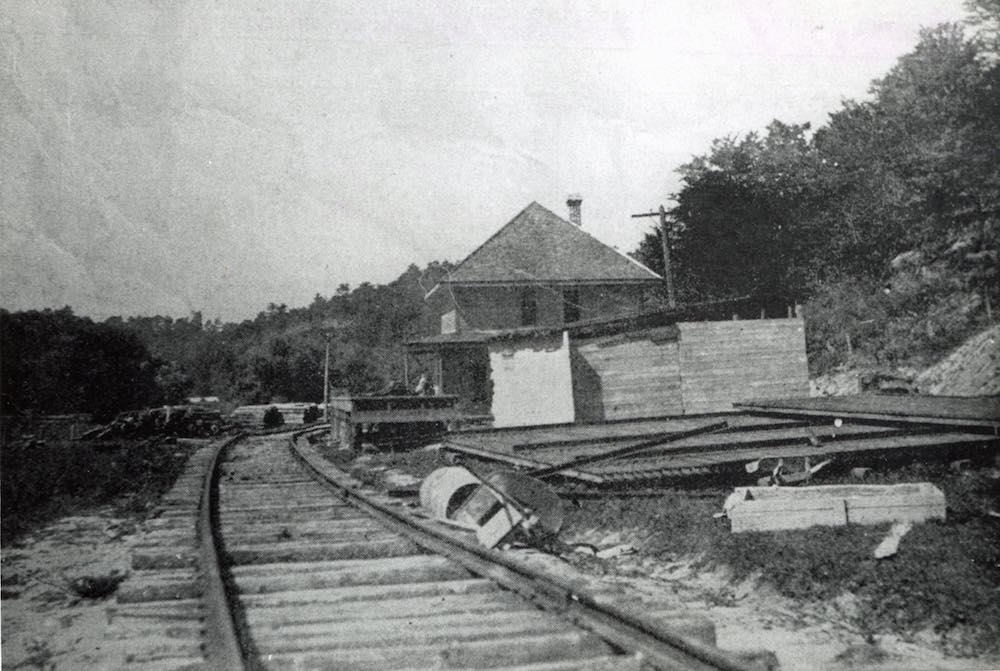

Battle of the Don Valley

On July 27th, 1904, it was reported that the Angus Sinclair Company of Toronto was contracted to construct the James Bay Railway from Toronto to Parry Sound. Construction began in September of that year, and work on all 240 kilometres (149 miles) was expected to be completed by the following September. The northern half of the route from Washago to Parry Sound would pass through the Canadian Shield; a land that often presented an engineering challenge due to its rocky and hilly nature combined with rivers, lakes, and muskeg. Dynamite was required to blast through the rock in numerous places. The terrain south of Washago would prove relatively easier though not without its challenges, particularly in navigating the Oak Ridges Moraine. At an elevation of 700 feet above Lake Ontario, a small community called Vandorf at the top of the moraine was selected for the turning of the first sod on September 14th, 1904. According to an edition of the Toronto World covering this event, the section of the James Bay Railway just north of Richmond Hill at Elgin Mills Road was expected to have one of the heaviest grades on the entire line. By January of the following year, an estimated 1,000 workers were involved in its construction.

As the year wore on, it became clear that the projected opening of September 1905 was a tad too optimistic. Much of the complications stemmed from the James Bay Railway’s entrance into Toronto through the Don Valley. It would be the last of three railways to occupy the valley, the others being the Toronto Belt Line and Canadian Pacific’s Don Branch. The Belt Line was a property of the Grand Trunk Railway that had been largely abandoned. The only exception was a short segment along the Don River as far north as Rosedale that was kept partially active into the early 1900’s. The narrow space along the river, particularly towards its southern end required both the GTR and CPR to share the same right-of-way south of Winchester Street. On November 7th, 1905, there was a meeting at Toronto’s City Hall over Canadian Pacific’s application to double-track their Don Branch, which was met with strong opposition from the James Bay Railway. The position of the company was laid out clearly by A. Y. Ruel, representing the JBR:

“If the application of the C. P. R. [will] be granted the construction of the second track would seriously interfere with an independent line for the James Bay Railway, which the company preferred, for the reason that any running rights which may be granted now would only be sufficient for five or ten years, and the exigencies of the traffic a few years hence were almost certain to require that the company have their own independent line”.

While the JBR preferred their own right-of-way separate from the CPR and GTR, it was the position of city officials that it should use the existing tracks of the other two railways.

Construction of the James Bay Railway pushed deeper into the Don Valley during the beginning of 1906. By February the work had almost reached the Don Valley Brickworks east of Rosedale. It was at this point that the JBR intended to cross a track belonging to the Grand Trunk. On February 16th, 1906, workers building the James Bay Railway would find a 30-ton coal hopper deliberately placed on this track in front of them. As the James Bay crew tried to move the hopper onto jacks in hopes of removing it, a Grand Trunk locomotive was driven down the spur and knocked the hopper off the jacks. A pit was then dug by the James Bay workers with the intent of pushing the coal hopper into it. The Grand Trunk engine returned and pushed another one of its cars into the hole instead. As the James Bay crew attempted to blockade the Grand Trunk spur to prevent further disruptions, a Grand Trunk crew began laying new track immediately to the south. Numerous scuffles broke out between the workers of the opposing companies. The incident, which numerous publications would refer to as a “war” or “battle”, ended with an explosion of dynamite that luckily didn’t result in any injuries.

“The Peaceful Don Valley was the scene of corporation strife yesterday which for real strategy and passion puts to shame its many Thanksgiving Day battles. Two great railway companies spent the day in fighting for a right of way, smashed several cars, rent the air with explosions and dynamite, and incidentally endangered the lives of a number of workmen. High officials of the Grand Trunk and the James Bay Railway Companies directing the opposing forces, which had several personal clashes, and when daylight ceased the Grand Trunk forces left the scene…”

The Hamilton Evening Times, February 7th, 1906

Residents of the nearby affluent neighbourhood of Rosedale were disturbed by the noise and city officials were similarly unimpressed. At the insistence of the city, the Grand Trunk allowed the James Bay Railway to use its Belt Line right-of-way southward from Rosedale. Even though the Grand Trunk was operating few if any trains over this segment of the Belt Line at this point in time, James Bay Railway trains were initially required to follow Grand Trunk operating rules over this segment. The Belt Line’s former Rosedale Station was to be adapted by the James Bay Railway as both a passenger station and divisional headquarters.

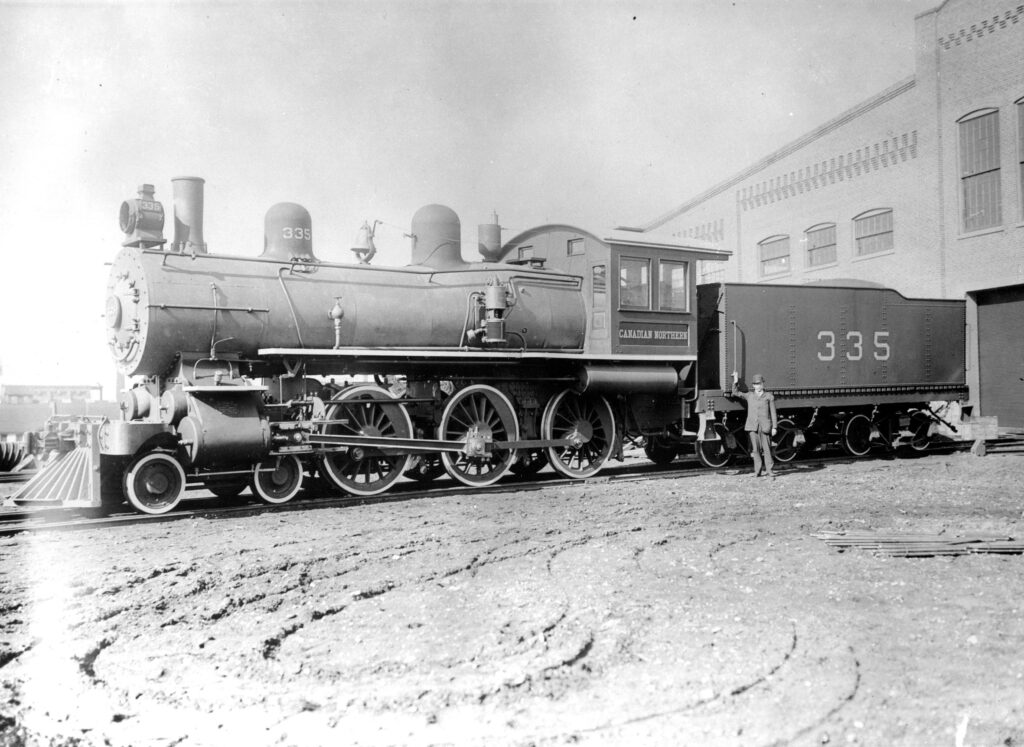

Toronto as a Canadian Northern Hub

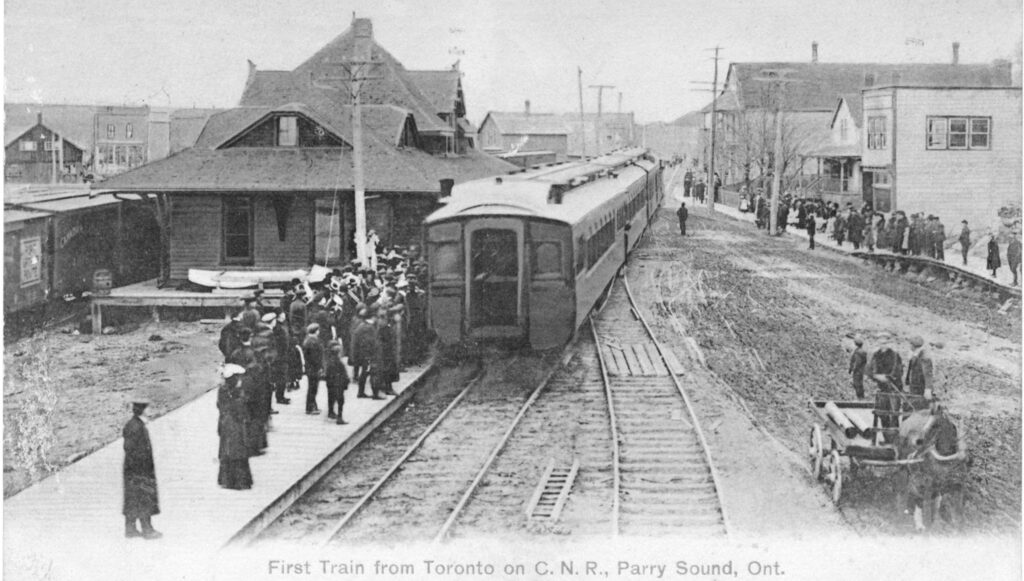

An uneasy peace ensued between the Grand Trunk and the James Bay Railway. Effective June 25th, 1906, the company was rebranded as the Canadian Northern Ontario Railway, cementing it as a local division of the broader Canadian Northern system. By August, the railway was reportedly completed with the exception of roughly six kilometres at the Toronto end of the line. Multiple new locomotives were sourced locally from the Canada Foundry in Toronto, some still lettered for the James Bay Railway upon delivery. Lacking the expansive passenger terminal facilities that it initially planned to have, an agreement was finally reached between Canadian Northern and the Grand Trunk Railway to share the existing Union Station on November 7th, 1906. In return, Canadian Northern was required to pay the Grand Trunk one dollar for each baggage, mail, express coach and sleeping car entering and leaving the station. This agreement was intended to be temporary until a permanent Canadian Northern passenger terminal could be established elsewhere in the city. After further delay, regular service finally began between Toronto and Parry Sound on November 19th, 1906. The first passenger train departed Parry Sound at 7:30am and arrived in Toronto at around 2:30pm, averaging a speed of about 34 kilometres per hour (21 miles per hour). Another passenger train left Toronto at 8:10am and arrived in Parry Sound at 3:00pm, reportedly with 50 passengers on board. While the opening of a new railway was far from novel for Toronto at this point, the opening of this railway massively sped up travel for people living in Parry Sound. The opening of Canadian Pacific’s line to Sudbury was another two years out.

Even before construction of the James Bay Railway began, Mackenzie and Mann were already looking to the places they would expand after it opened. Southwestern Ontario in particular was being eyed as early as 1902. On November 22nd, 1906, just three days after the Toronto-Parry Sound line’s opening, the Toronto World announced that a new Canadian Northern line from Toronto to Ottawa along the shore of Lake Ontario was already being surveyed. It was initially reported that construction would begin as soon as the following April, and an application for government approval of the route was made on January 16th, 1907. Once April arrived, it was reported that the Toronto-Ottawa line would be delayed due to problems the Canadian Northern Railway was encountering in Western Canada. In the meantime, further developments along the Toronto-Parry Sound line were being made, particularly of the tourism variety. Steamship docks were built at Lake Joseph and Bala, and a seasonal passenger service was inaugurated between Toronto and Parry Sound on June 13th, 1908, with the express purpose of bringing wealthy tourists and sportsmen to these destinations. The Toronto-Parry Sound line was opened to Sudbury the following month, bringing it slightly closer to a connection with the broader Canadian Northern system in the prairies.

A major problem that would need to be tackled swiftly was establishing proper terminal facilities in Toronto. Upon opening in 1906, Canadian Northern’s freight locomotives were originally serviced at the Grand Trunk roundhouse in Danforth, while passenger locomotives were serviced at the Grand Trunk’s other roundhouse near Spadina Avenue. Land was purchased for temporary yards adjacent to Rosedale Station in 1907, but this location was undesirable for a variety of reasons. Chief among them was the Don River’s tendency to flood each spring. On at least one occasion it left several Canadian Northern employees stranded on the roof of the Rosedale enginehouse. Plans were drawn up for a new seven-stall roundhouse at the corner of Eastern Avenue and Cherry Street on May 7th, 1908, but the land became occupied by freight sheds instead. Simultaneously, Mackenzie and Mann had been trying to identify a suitable location for backshops capable of maintaining all locomotives and rolling stock on the Canadian Northern’s eastern lines. Toronto was eventually chosen over Montreal, but a few locations within the city were under consideration.

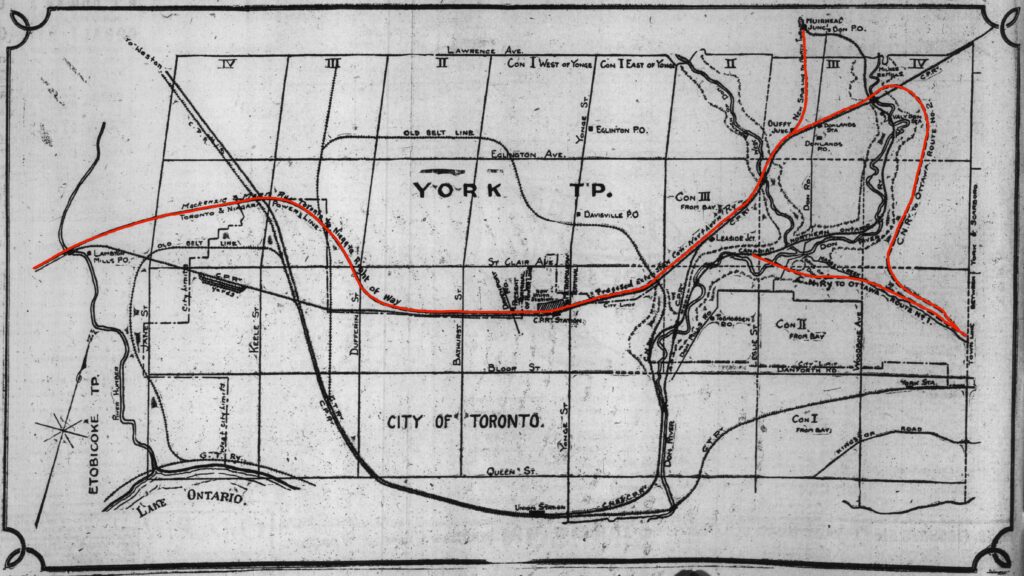

Mackenzie and Mann set their sights on the North Toronto area just before the end of the decade. This neighbourhood was already crossed by the mainline of the Canadian Pacific Railway, who were coincidentally aiming to revitalize their existing passenger facilities at North Toronto at the same time. North Toronto would make for an ideal location to link Canadian Northern’s existing line north of the city as well as the proposed lines to the east and southwest. Furthermore, it would present an opportunity for the Canadian Northern to construct repair shops on higher ground, allowing them to abandon much of their trackage in the Don Valley and avoid the flooding issue entirely. Canadian Northern initially proposed to run their right-of-way parallel along the north side of the Canadian Pacific line, but the city opposed this on the grounds that it would exacerbate the safety issues caused by the many grade crossings in that area. These plans were largely kept secret from the public; the Toronto World first reported what it described as “mysterious” property purchases in North Toronto on September 30th, 1909, stating that these seemed to corroborate local rumours of a new Union Station in the area. More details would gradually reach the public over the next few years. Donald Mann confirmed in a 1909 interview that the repair shops would not be built until after the separate Canadian Northern systems were joined through Northern Ontario, as well as the opening of the Toronto-Ottawa line.

Delays & Funding Issues

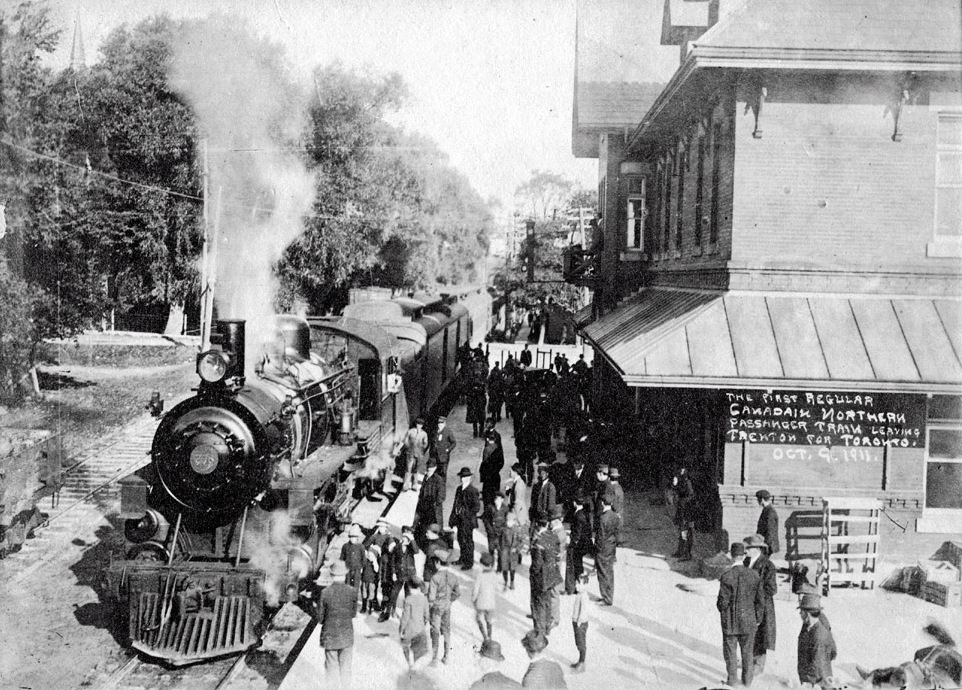

After a delay of three years, construction of the Canadian Northern’s Toronto-Ottawa line commenced in January 1910. Much like the James Bay Railway, the work was once again contracted to the Angus Sinclair Company. Work camps were set up in multiple places along the right-of-way and some preliminary work was conducted immediately. Concrete culverts and bridge abutments were some of the first things to be built, with the work ramping up as the ground thawed in the spring. By March it was said there were a total of 700 employees working at various points. As a temporary measure, the Toronto-Ottawa line originated at a point in the Don Valley near Todmorden Village and ascended through Taylor Creek. The latter is where some of the heaviest earthwork on the line was conducted, requiring the use of a steam shovel. The line was to feature an impressive number of high-level steel trestle bridges as a result of crossing several river valleys at their widest points. The longest of these was built across West Duffins Creek north of Pickering, measuring 259 metres (850 feet) in length. Trenton was reached in 1911 due in part to the purchase of the Central Ontario Railway by Canadian Northern, using them as both an eastward stepping stone and making use of their access to raw resources. The long-anticipated first train between Toronto and Trenton made its run on October 9th, 1911. A special train was to depart westbound from Trenton to Toronto and then return east. It allowed free admission and included two passenger cars for each town and one car for each village along the route. An article from the Canadian Statesman noted a dozen cars in the consist. Following the special train, the first regular scheduled passenger trains also commenced later the same morning. The Toronto-Ottawa line would finally open for regular service to Ottawa two years later on October 3rd, 1913.

If a terminal was to be established at North Toronto for Canadian Northern, it would require the western end of the Toronto-Ottawa line to be rerouted entirely. While the proposed route would have circled the valley edge before crossing with a high-level bridge east of Leaside. The bridge in question would have been longer than any of those already built on the Toronto-Ottawa line, and its prohibitive price tag was too much for Mackenzie and Mann. Despite its explosive growth over the past decade, the cracks were starting to show in the Canadian Northern’s finances. Regardless, the pair continued planning further expansions around Toronto. The proposed line into Southwestern Ontario, originally only intended to go to Hamilton, was extended to Niagara Falls with an additional line to Windsor. At the Toronto end of the line, it would make use of a hydro corridor right-of-way already established by the Toronto Power Company. A planned 2,360-foot tunnel beneath the Grand Trunk’s Northern & North-Western Division at Davenport Station would have precluded the use of traditional steam engines, so the hydro corridor would have been leveraged to use electric locomotives instead. It’s unknown what this equipment would have looked like as they were never ordered, though the scheme bears some similarities to the Mount Royal Tunnel in Montreal which the Canadian Northern was having built around the same time.

In November 1911, the Board of Railway Commissioners upheld the City of Toronto’s efforts to prevent Canadian Northern from laying their tracks parallel to Canadian Pacific through North Toronto. The two railways were ordered to build a shared elevated rail corridor, the cost of which would also be shared between both companies. The corridor was to be wide enough to support the double-track lines of both railroads, as well as sidings for the many industries popping up in this part of the city at the time. Construction on the corridor began in 1912, and ground broke on the new North Toronto Station in the spring of 1913. Canadian Pacific would be responsible for its construction and maintain ownership of the building, while Canadian Northern would pay Canadian Pacific for tenancy of the station. Separate ticket offices for both railroads were included in the plans. While Canadian Pacific only intended to use the North Toronto facility for certain trains, virtually all of Canadian Northern’s passenger service was to be based out of it.

In 1911, Canadian Northern interests purchased 1,000 acres of farmland immediately to the north of the Canadian Pacific station at Leaside. While much of this land was to be reserved for Canadian Northern’s long-anticipated Eastern Lines Shops, part of it was intended for a planned community to help fund the project. The Town of Leaside, as it was called, was incorporated in 1913. As the new repair shops were underway, the Minister of Railways approved Canadian Northern’s 7.2-mile line connecting their Toronto-Ottawa line with North Toronto Station. It couldn’t come fast enough as the Rosedale Yard reached its greatest extent, and the smoke and railway activity in the valley drew the ire of powerful and wealthy residents of Rosedale to the northwest. Even Canadian Northern’s Vice-President David Hanna, a resident of Rosedale himself, relocated to move away from the noise in the valley below.

Decline of the Canadian Northern Railway

In the May 8th, 1913 edition of the Toronto World, the newspaper published a statement from William Mackenzie concerning his recent visit to England. His outlook on the company was optimistic, at least publicly:

“Notwithstanding mischievous reports to the contrary, I have returned from the borrowing centre of the world feeling just as confident as ever over the success of the Canadian Northern enterprise”.

Unbeknownst to him at the time, the financial condition of his company was about to get even worse. On August 4th, 1914, the British Empire declared war on Germany, thereby bringing Canada into World War One due to its status as a British Dominion. This global event would have far-reaching consequences across the entire railway industry in Canada, and the Canadian Northern Railway was no exception in this regard. Its funding from European investors dried up as the war took hold overseas. As much of the workforce left for Europe and materials were diverted, efforts to construct the Eastern Lines Shops in Leaside were halted immediately. Critical infrastructure projects, or ones that were already almost complete, were pushed ahead at a reduced pace. The separate Canadian Northern systems in Ontario and the prairies were finally joined in August 1915. With William Mackenzie on board, the inaugural train arrived in Vancouver on August 27th in a record 91 hours. Revenue passenger service between Toronto and Vancouver did not commence until a few months later on November 19th, 1915.

As the Canadian Northern’s finances worsened, a local dispute with the Grand Trunk came to a head. The Canadian Northern was informed that, effective March 26th, 1915, the Grand Trunk would cease to accommodate their use of old Union Station. The reason cited by the Grand Trunk was that the Canadian Northern hadn’t paid the agreed-upon fee for rolling stock entering or leaving the station since 1907. During a hearing held in Toronto, Canadian Northern officials argued that the Grand Trunk had similar outstanding payments for its use of the Union Station in Edmonton, Alberta going back to 1909. When it was found that the amounts due to each company were almost equal, the Grand Trunk reluctantly agreed to continue to uphold its accommodation of the Canadian Northern in Toronto.

While the overcrowding at Union Station was quickly becoming unbearable, work on the new North Toronto Station was progressing. A connection from either of the Canadian Northern lines to the new passenger terminal seemed less likely than ever, but Canadian Pacific was upholding its end of the deal regardless. On October 1st, 1915, the two companies entered an agreement for the joint use of the station as well as the elevated corridor, both of which were nearing completion. The Canadian Northern Railway would be given exclusive rights to traffic from industries on the north side of the corridor west of North Toronto Station, while Canadian Pacific would have similar rights on the south. East of the station, both railways would make use of common tracks as far as Leaside. An official opening ceremony for North Toronto Station was held on June 14th, 1916, though service had already begun ten days prior. Since Canadian Northern was still physically unable to bring their trains into the new station, Canadian Pacific was the only railway offering passenger service there upon opening.

Unfortunately for Canadian Northern, most of the gains from wartime traffic were seen by its rivals. A sentiment to that effect is echoed by a 1917 report on the Canadian Northern by a special council: “Existing traffic between Vancouver and Edmonton, while growing rapidly, is negligible at present.” And “Existing traffic between Port Arthur, Ottawa and Montreal, is also negligible at present”. Perhaps most pressing, the company’s financial situation threatened the solvency of its largest investor, the Canadian Bank of Commerce. While the Canadian Northern was in rough shape, it was not the only one. The Grand Trunk Railway was facing similar problems due in no small part to its transcontinental ambitions. On July 20th, 1915, Toronto World published a report on the state of railway companies in Canada. It is prefaced with the following: “We do not know of anything that has gripped the public mind like the proposal that the Canadian Government should take over and nationalize the Canadian Northern, and then the Grand Trunk Pacific”. As the quote suggests, there was much debate at the federal level over whether the government should gain control of these railways. The motivation behind nationalization varied in the other places they were tried; Britain had already begun managing its railways in 1914, and the United States would do something similar with their formation of the United States Railroad Administration in 1917. This was generally done to improve efficiency to meet the crushing demands of wartime; by operating disparate railway companies as a single, cohesive unit. In the case of Canada, however, the prevailing argument was that since Canadians’ tax money had subsidized so much of the ailing Canadian Northern, it ought to be owned by the people of Canada as well. The Honourable George P. Graham, parliamentary representative for Renfrew South at the time, had an especially fitting quote on the situation in 1916:

“We are handing out money year after year and have nothing to show for it except 40 per cent of the Canadian Northern stock, which I imagine would not make anybody rich on the stock exchange at the present time”.

After it was found that the Canadian Northern’s liabilities were worth more than its assets, the federal government took control of the railway on August 1st, 1917. Work would finally resume on the Leaside repair shops and a connection between North Toronto and the Toronto-Parry Sound line, but no such effort was made on connecting the Toronto-Ottawa line. The line to Hamilton and beyond was similarly never built. Effective September 6th, 1918, William Mackenzie and Donald Mann were required to resign from the Board of Directors. In the words of the Prince George Star:

“Sir William Mackenzie, head of the company, promptly went to Ottawa and had himself taken out of the hands of the new officials of this province by having the C.N.R. declared to be an undertaking for the benefit of all Canada”.

There were already some railways under federal control at this point in time, notably the Canadian Government Railways which itself had only formed three years earlier. Its purpose was to consolidate the federal government’s other railways: the Intercolonial Railway of Canada, National Transcontinental Railway, Prince Edward Island Railway and the Hudson Bay Railway, under a single managing body. On December 20th, 1918, a Privy Council order directed the Canadian Northern Railway and the Canadian Government Railways to be managed under the name Canadian National Railways as a means to simplify funding and operations. The Canadian National Railways was incorporated as a crown corporation on June 6th, 1919.

While neither Canadian Northern nor Canadian National passenger trains ever served North Toronto Station, the connection from the Toronto-Parry Sound line was completed under the latter in September 1918. This enabled access to the Eastern Lines Shops, which were finally opened on June 9th, 1919. Due to a variety of factors post-nationalization, these repair shops were very underutilized and parts of it were abandoned as early as the 1930’s. The locomotive erecting shop, which has since been readapted into a grocery store, is the only part of the Eastern Lines Shops that remains today. The Rosedale Yards were officially abandoned on June 26th, 1920, and the area has largely been reclaimed by wilderness. While the Toronto-Parry Sound line maintained its relevance as an important artery under Canadian National, the Toronto-Ottawa line was not so lucky. The majority of it was abandoned in sections between 1924 and 1938, while other parts were abandoned in the 1980’s and 1990’s. Only the segment from Smiths Falls to Ottawa is actively used today.

Written by Adam Peltenburg.

References

Address of Hon. E.J. Davis, Commissioner of Crown Lands, on the completion of the Port Arthur section of the Canadian Northern. (1902). Canadiana Online. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.86659/3

Canadian National Railways Accounting Department, Hopper, A. B., & Kearney, T. (1962, October 15). The Canadian Northern Ontario Railway Company. Synoptical History of the Canadian National Railway Company, pg. 183-186. https://railwaypages.com/cnr-synoptic-history-to-1960

Canadian Pacific Ry. Co. v. James Bay Ry. Co. (1905, April 06). Supreme Court Judgments. Supreme Court of Canada. https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/15203/index.do

Jackson, J. A. (2010, July 23). The Background of the Battle of Fort Whyte. Manitoba Historical Society. http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/transactions/3/fortwhyte.shtml

The James Bay Railway. (1897). Canadiana.ca, pg. 17. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.07525/8?r=0&s=1

Robertson, F. B. (1887). Railway Monopoly: Letters Addressed to the Toronto Mail by F. Beverley Robertson and The Effects of Monopoly. Canadiana.ca, 13. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.30474/6?r=0&s=4

Souvenir of the banquet given by the Board of Trade of the City of Toronto, to Wm. Mackenzie, D.D. Mann, and the Canadian Northern Railway. (1906, December 14). 18.

The Toronto World. 1904. “Mackenzie-Mann Spring a Mine; Will Expropriate Burned Area.” July 5, 1904. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19040705/2.

The Toronto World. 1904. “Grand Trunk Now Returns To Its First Proposition.” September 14, 1904. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19040914/1.

The Toronto World. 1904. “James Bay Railway Will Break First Sod To-Day.” September 14, 1904. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19040914/2.

The Hamilton Evening Times. (1906, February 07). Railways War In Don Valley. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00138_190601/309.

Hamilton Evening Times. 1906. April 30, 1906. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00138_190601/987.

The Toronto World. 1906. “New Line Opens Monday for Passenger Service.” November 14, 1906. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19061114/3.

The Toronto World. 1906. “C.N.O. Surveyors Busy on Ottawa-Toronto Line.” November 22, 1906. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19061122/3.

The Toronto World. 1906. “The Trip to Parry Sound over the Newest Railway.” November 22, 1906. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19061122/3.

The Toronto World. 1907. “Toronto-Ottawa Line.” April 26, 1907. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19070426/12.

The Toronto World. 1908. “C.N.R. Summer Service.” June 3, 1908. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19080603/1.

The Toronto World. 1909. “Railway Move to North End Coming.” September 30, 1909. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19090930/1.

The Toronto World. 1912. “Start On Union Station First Thing Next Spring.” November 7, 1912. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19121107/1.

The Toronto World. 1913. “Future of C.N.R. Bright, Says Mackenzie.” May 8, 1913. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19130508/1.

The Toronto World. 1913. “Toronto’s Greatest Subdivision; Leaside An Extension of Rosedale.” May 30, 1913. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19130530/12.

“Canadian Railway and Marine World.” 1915. In The Canadian Northern Railway’s Use of Toronto Union Station. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_06968_40/30.

The Toronto World. 1915. “How Nationalization Will Improve a Bad Mixup.” July 20, 1915. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19150720/6.

The Toronto World. 1918. “Marooned On Top of Roundhouse.” February 26, 1918. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19180226/1.

“Canadian Railway and Marine World.” 1919. In Shops, Yard, Etc., Canadian National Railways, At Leaside, Near Toronto. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_06968_83/1.

The Toronto World. 1920. “National Railways Leave Don Valley.” June 26, 1920. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19200626/3.