The Battle of the Don Valley

In the year 1880 there were five separate railway companies serving Toronto simultaneously. Almost all were snatched up by mergers and acquisitions until only two remained at the turn of the century: the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Grand Trunk Railway. When the upstart Canadian Northern Railway tried to join them in the Queen City just a few years later, one could say the results were… explosive. Regulations against monopolies and anti-competitive behaviour in Canada were minimal at best during this period, and it wasn’t unheard of for railway companies to engage in open hostilities when they felt their profits were threatened. As is noted in this website’s writeup on the Credit Valley Railway, there was an earlier incident in which the Grand Trunk physically obstructed a Credit Valley project in Toronto’s west end by erecting barricades of rolling stock and other debris. The Canadian Pacific Railway wasn’t a stranger to this behaviour either, with the so-called Battle of Fort Whyte in Manitoba perhaps being the most well-documented example. In today’s blog post we’ll be talking about an event I call the Battle of the Don Valley. That name might sound sensational – partly why I like it so much – but it honestly isn’t far off what newspapers from the time were calling it. This historical event is something the TRHA has previously covered in short-form social media posts, but I thought it was deserving of something more in-depth. As we will explore, the battle only represents the climax of a multi-year escalation between the Canadian Northern and Grand Trunk Railway systems.

Setting the Scene

The Grand Trunk was by far the older of the two railways left serving Toronto at the turn of the 20th century, having enjoyed a near-monopoly on through traffic in much of Ontario until the arrival of the Canadian Pacific Railway in the mid-1880’s. From the moment the latter was formed, the two were essentially in a race to buy up the smaller railways in the Toronto area until none were left. That is, until entrepreneurs William Mackenzie and Donald Mann entered the picture. We have a more comprehensive writeup on their Canadian Northern Railway and its history in the GTA elsewhere on this website, but this post is going to focus on a very specific facet of the Mackenzie and Mann empire at a very early stage in its history. In fact, this story technically begins a decade or more before the Canadian Northern Railway even existed.

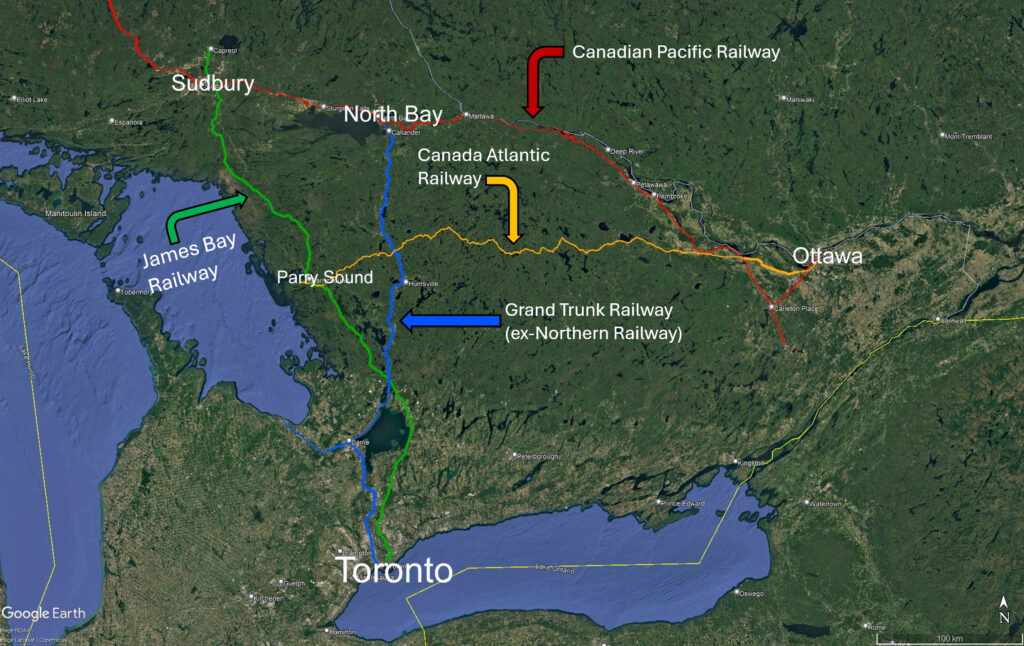

We start with the Nipissing & James Bay Railway, which was chartered in 1884 to build from the vicinity of North Bay to the shore of James Bay – about the same route that the Ontario Northland Railway currently runs from North Bay to Moosonee. One could argue that the Nipissing & James Bay was ahead of its time – the North Bay area didn’t even have any rail service at the time it was chartered. The Canadian Pacific Railway was still a year out from opening its transcontinental route through that part of the province, and it would be another year after that for the Northern & Pacific Junction Railway (N&PJ) to open between North Bay and Gravenhurst. The latter of the two was essentially an extension of the Northern Railway of Canada. The thinking behind the Nipissing & James Bay Railway was that its connection with the N&PJ would essentially create a continuous rail connection between potential shipping routes in Hudson Bay and those in the Great Lakes. This idea of a portage railway wasn’t all too different from what the Northern Railway did between Toronto and Collingwood three decades earlier, though this would naturally be a more ambitious undertaking. It was also hoped by the company’s directors that the connection to both the N&PJ and Canadian Pacific would encourage increased colonization of the northern reaches of Ontario. Neither William Mackenzie nor Donald Mann were involved in the Nipissing & James Bay Railway at this early stage – they would have been working as contractors helping to build the Canadian Pacific Railway out west at the time. After William Mackenzie moved to Toronto in 1889, he formed the Toronto Railway Company and successfully won a 30-year contract to operate the city’s streetcar system in 1891. The provisional directors of the Nipissing & James Bay Railway were mostly prominent businessmen from Toronto; it’s likely this is when Mackenzie became involved with that project.

By this point, their charter had existed for nearly ten years with virtually nothing to show for it. The Nipissing & James Bay’s backers now hoped the Grand Trunk Railway (who gained control of the Northern in 1888) would pick up the charter or lease it and assist with construction, ultimately to take over operations once completed – but they didn’t bite. In February of 1895, the directors met in Toronto to discuss what to do with their railway. The attendees were kept anonymous in news reports from the time, but I’m willing to bet that William Mackenzie was among those in attendance. In any case, the final verdict was that they would start their own railway in lieu of support from any others. Five months later, on July 22nd, 1895, the James Bay Railway was incorporated. William Mackenzie and Donald Mann were among those listed as provisional directors of the company.

The initial charter of this new company stipulated a route from Parry Sound to James Bay via Sudbury. This way it would connect with the Canadian Pacific Railway at Sudbury and the Canada Atlantic Railway at Parry Sound while effectively cutting out the Grand Trunk. However, a couple of years later the directors decided to take their plans one step further. In an 1897 letter addressed to the Attorney-General of Ontario, three of the individuals behind the James Bay Railway stated their company’s intentions to build all the way from James Bay to Toronto. It would follow the same route from the 1895 charter between James Bay and Parry Sound, but now threatened to offer stiff competition to the Grand Trunk rather than simply avoiding them. At this point in time westward travel was somewhat limited from a Torontonian perspective. The Grand Trunk line to North Bay was the most direct all-Canadian route west for many people living in southern Ontario, the only other options being several layovers and two international border crossings through the United States, steamships on the Great Lakes, or a nearly 300 kilometre jog to Carleton Place via Canadian Pacific before you would start moving west. The CPR did secure running rights over the Grand Trunk line to North Bay on occasion but it was promptly taken away whenever the two companies engaged in hostilities. According to individuals associated with the James Bay Railway, they believed their route would shave three hours off travel time once completed.

Stirring the Pot

Ironically, some give credit to the early hype around the Grand Trunk Railway’s pacific extension for reviving interest in the James Bay Railway to begin with. By 1903, its route was slightly altered once more to terminate at an unspecified location on the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway* rather than James Bay. However, the relationship between the two companies would dramatically change over the course of the next few years. The competitive nature of the James Bay Railway’s route was bad enough, but through either perceived necessity or hubris or a combination of the two, Mackenzie and Mann would seemingly go out of their way to egg on the Grand Trunk in particular. The Great Fire of 1904 burned out a considerable chunk of downtown Toronto, and the now-vacant land was quickly eyed by the Grand Trunk as a solution to their overcrowding problems with old Union Station. However, to just about everyone’s surprise, the growing Mackenzie and Mann outfit (seemingly) beat them to the punch:

“Mayor Urquhart announced to the board of control yesterday that the Canada [sic] Northern Railway had filed plans at Ottawa providing for an entrance into [Toronto] and for passenger terminals, which would expropriate the entire district which had been under discussion as a site for a new Union Depot. W. H. Moore, assistant to President Mackenzie of the C.N.R., was present, and stated that before giving particulars he wished to have the board confer with D. D. Mann, and an appointment was made for to-morrow. The announcement came as a startling surprise to the controllers, and, in fact, was the topic of conversation on the streets during the afternoon. The general opinion was that the C.N.R. had played a trump card”.

The Toronto World, July 5th, 1904

* East of Winnipeg the Grand Trunk Pacific was built federally under the banner of the National Transcontinental Railway, which was intended to be absorbed by the Grand Trunk after it was finished. For the sake of simplicity I’ll be referring to it only as the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway.

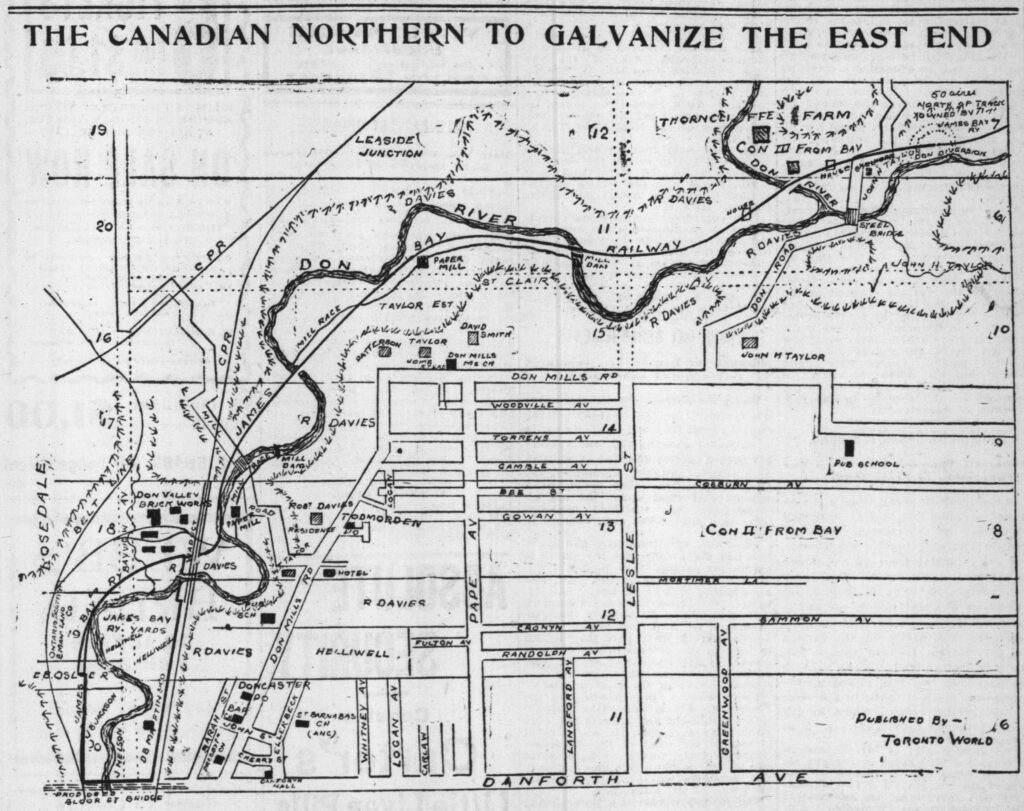

It should be noted that by this point, the route that the James Bay Railway would take to reach Toronto was only recently made public. The move caught most by surprise including both the Grand Trunk and Canadian Pacific. According to the same article the above excerpt is from, the James Bay Railway sought to enter Toronto via the Don Valley. This would require squeezing down the west side of the lower Don River next to the former Toronto Belt Line. By this point most of the Belt Line was sitting unused except for a small section in the Don Valley – an important point that’s going to come up later. The quotes from an interview with William Mackenzie in the article alongside the editorializations from the author portray him as a little overconfident to put it lightly. When asked, Mackenzie replied that he “had not been aware” of the Grand Trunk’s plans for a new Union Station on the same site that he chose. Describing his motivations for acquiring the site as purely pragmatic, the author notes Mackenzie replied with “one of his inscrutable smiles”. The interview ends with Mackenzie’s answer to a question about his company’s relationship with the Grand Trunk and Canadian Pacific in light of this new development:

“I don’t think there will be much change. We are on quite as good terms with the C.P.R. as the G.T.R.,” replied the Canadian Northern president with a humorous twinkle in his eye. “We are all very good friends.”

The Toronto World, July 5th, 1904

These editorializations were included for a reason. Towards the end of the article, the author notes that the Grand Trunk Railway was the first company to submit their application for expropriating the land – beating Canadian Northern by a matter of days. Mackenzie knew this but believed that his company would be given priority due to some technicality in the railway act, but this ultimately didn’t pan out. The future site of Toronto Union Station went to the Grand Trunk and that company’s name remains engraved on its walls today, whereas Canadian Northern is nowhere to be found.

As if the aggressive behaviour wasn’t enough, the plans for the James Bay Railway changed once again at the beginning of 1905 in such a way that would cut out the Grand Trunk Pacific altogether. The proposed James Bay route was shortened further to Sudbury, while Mackenzie and Mann were simultaneously petitioning parliament for the ability to construct another railway line from Sudbury to Port Arthur (Thunder Bay). Not only would this somewhat duplicate the proposed Grand Trunk Pacific Railway through northwestern Ontario, it would directly connect the James Bay Railway to the broader Canadian Northern system in the prairies. Given that the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway was proposed to run through some of the most remote parts of Ontario and Quebec, a considerable amount of its profitability would be reliant on through traffic to/from out west. If Mackenzie and Mann followed through with this competing route, it threatened to split through traffic three separate ways.

The Grand Trunk Railway’s Response

The ball was now firmly in the Grand Trunk’s court. Just two months after Mackenzie and Mann’s Union Station shenanigans, it was announced that the Grand Trunk Railway was gaining control of the Canada Atlantic Railway (CAR) in late 1904. The CAR connected the James Bay Railway at Parry Sound with its Georgian Bay port at Depot Harbour, the federal capital of Ottawa, and Algonquin Park among other things. Mackenzie and Mann sought to gain control of the Canada Atlantic both for its tourism appeal and to connect their Canadian Northern system with eastern Canada – and now the Grand Trunk had essentially carried out the same maneuver their rival failed to execute with Union Station. Some suggested that acquiring the Canada Atlantic would enable the Grand Trunk to start its pacific extension without laying a single new rail east of North Bay, though this wasn’t the case. The acquisition was nonetheless beneficial to the Grand Trunk but according to an anonymous “prominent railway man” interviewed by the Toronto World, this move was done explicitly to “check Mackenzie and Mann”.

To both the C.P.R. and Mackenzie and Mann this move came as a rude surprise. The C.P.R. saw at once [the Grand Trunk] was acquiring the Canada Atlantic as a means of hastening its entrance into the west. Mackenzie and Mann were anxious to get the Canada Atlantic, which would have given them a summer line of transportation between Winnipeg and Quebec. They had counted on getting the [Canada Atlantic], and believed that they had the co-operation of the government in their plans for taking over Mr. Booth’s road.

The Toronto world, September 14th, 1904

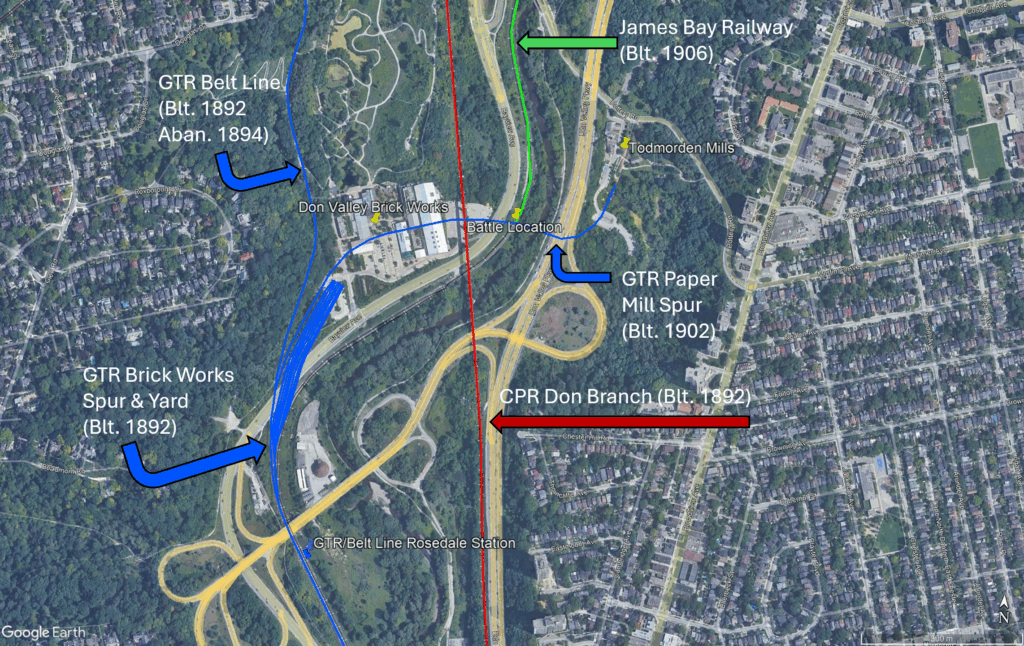

Even though the James Bay Railway had planned out its route into Toronto long before construction began, the situation in the lower Don Valley was somewhat complicated. When the Toronto Belt Line encircled the city with its commuter-focused Yonge Loop in 1892, a short industrial spur was built to provide freight service to the Don Valley Pressed Brick Company (now the site of the Evergreen Brickworks). Since the Grand Trunk owned the Toronto Belt Line, it continued bringing freight trains up to that point in the Don Valley after the rest of the Belt Line was abandoned in 1894. In about 1901-1902, the spur was extended through the brickworks property and underneath the “half mile bridge” of Canadian Pacific’s Don Branch to reach the lower John Taylor paper mill (now the Todmorden Mills Heritage Site) a short distance to the east. Some documentation suggests that it followed the path of a road that already existed between the brickworks and the paper mill. This track was obscure and short-lived; the incident in question provides some of the only evidence I’ve been able to find that it even existed. However, it seems it was the source of some controversy a short time before the subject at hand. Since Canadian Pacific owned the land below their bridge, they tried to sue the Grand Trunk for trespassing in 1905. They also argued that the spur was approved by the railroad commissioners without sufficiently involving them or the James Bay Railway. Despite this, the Grand Trunk won on the grounds that the spur had been operating for years without issue.

Whether due to obstruction from the Grand Trunk or some other reason, the James Bay Railway took a while to contest the Grand Trunk paper mill spur. On September 25th, 1905, it was reported that the James Bay Railway’s construction crews had only just gained access to land belonging to the Thorncliffe Farm, located close to where Don Mills Road crosses the Don River about three miles out from the spur. Reportedly fearing that their rights were in danger, the Grand Trunk Railway placed a hopper loaded with coal directly where the James Bay right-of-way was projected to come across the spur. Sources differ on the specifics; this occurred at some point between November 1905 and early January 1906. Some say the car contained 30 tons of coal, others say as much as 50 or 80 tons. In any case, the rails were then taken out from underneath so that the hopper would rest on the ties, making it more difficult to remove. It seems this largely went unnoticed as no efforts to remove the coal hopper were made until almost two months later.

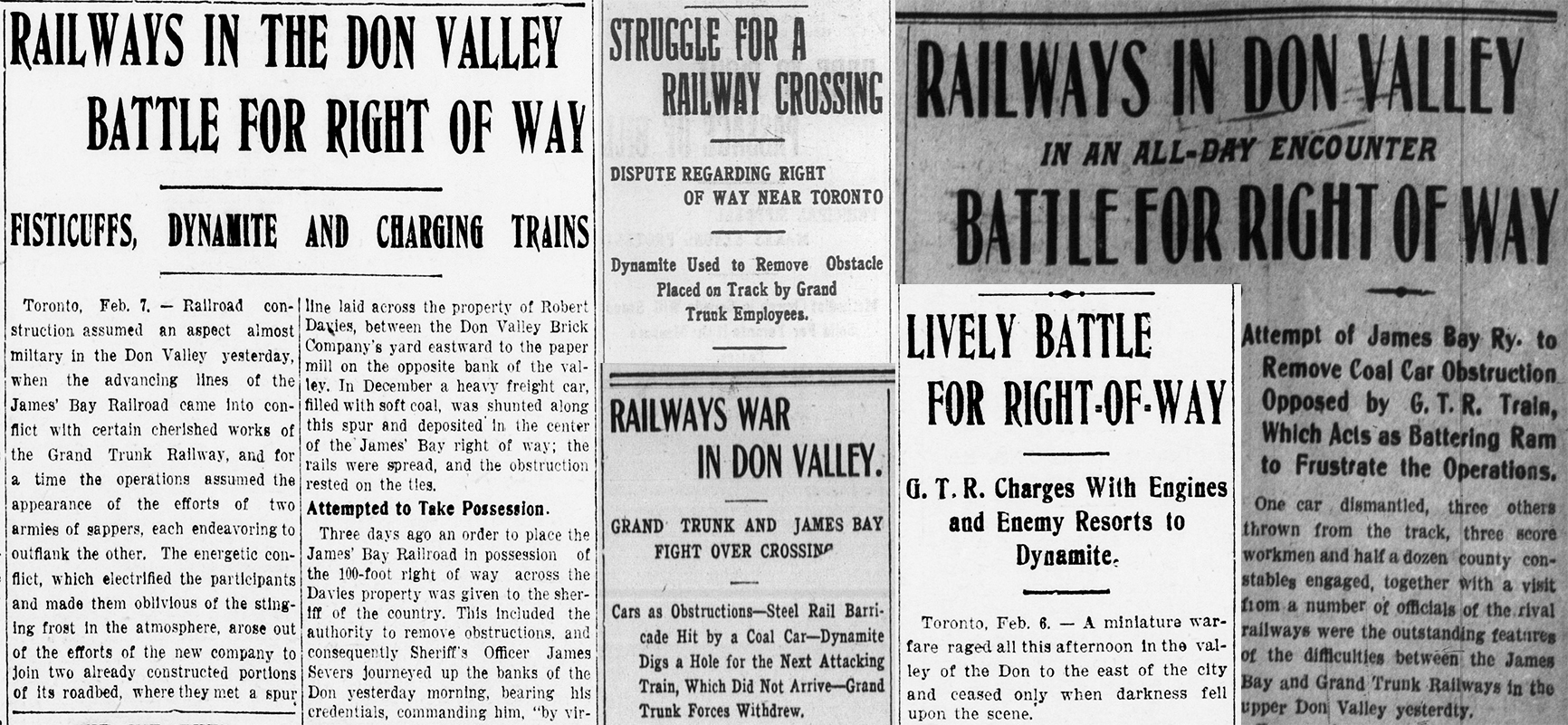

On February 4th, 1906, an order to place the James Bay Railway in possession of the land crossed by the Grand Trunk spur was given to the county sheriff. On the morning of February 6th, a gang of about 25 labourers backed by a county constable used jacks to raise the coal hopper and move it out of the way. At some point while the work was ongoing, the labourers might have spotted a plume of smoke working its way up the Don – the unmistakable chugging sound of a steam locomotive echoing through the valley. It would have made its way through the brickworks’ property before they could make out exactly what it was: A Grand Trunk work train with about 25 of their own labourers and W. G. Brownlee, superintendent of the Grand Trunk’s middle division on board. These workers weren’t here to build anything, though. The train was moving in reverse with several more loaded coal cars just like the one the James Bay workers were trying to clear. As the train got closer it became obvious that they had no intention of slowing down in time. The Grand Trunk train slammed into the first coal car and knocked it off the jacks, and an additional coal car was deposited by the train shortly after. As the train pulled back, the James Bay crew regrouped and began piling earth and 80-pound rail into a makeshift barricade – by no means an easy task while the ground was still frozen. However, they were interrupted by Grand Trunk labourers approaching on foot. A combination of words and fists were then exchanged between them and the James Bay crew.

“Railroad construction assumed an aspect almost military in the Don Valley yesterday, when the advancing lines of the James’ Bay Railroad came into conflict with certain cherished works of the Grand Trunk Railway, and for a time the operations assumed the appearance of the efforts of two armies of sappers, each endeavoring to outflank the other. The energetic conflict, which electrified the participants and made them oblivious of the stinging frost in the atmosphere, arose out of the efforts of the new company to join the two already constructed portions of its roadbed, where they met a spur line laid across the property of Robert Davies, between the Don Valley Brick Company’s yard eastward to the paper mill on the opposite bank of the valley.”

The London Advertiser, February 7th, 1906

In the meantime, the James Bay workers were able to lift the first coal car back onto the rails. That’s when the Grand Trunk train began to accelerate in their direction again – even against verbal warnings from the constable. It sliced through the barricade like nothing and left two additional coal cars in the way before pulling back once more. The Grand Trunk workmen then noticed that the James Bay crew were able to get the first coal car back on the rails and realized they would need to create a more permanent obstruction if they wanted to keep this up. Armed with rail and ties from their work train, the Grand Trunk labourers began hastily constructing a new track along the south side of the paper mill spur. The James Bay crew then tried building another barricade for the new set of tracks, far more substantial than the last. As the train doubled back and reversed, the barricade was able to hold and the next coal car was thrown from the tracks altogether. Seemingly still on the backfoot, the James Bay crew had one more card up their sleeve to make some headway. While all of this was happening, some spent the better part of that afternoon placing sticks of dynamite in the ground. Then, finally, the plunger was pushed. The resulting explosion sent workers on both sides running “confusedly to shelter” as the London Advertiser put it, and also created a hole in the ground that measured 60 feet across. The sound echoed through the valley and could be heard in what was then the northeastern outskirts of Toronto. Miraculously, no one was injured. Sources differ on the James Bay workers’ goal but it was either to clear the debris directly with the dynamite or create a trench that would prevent the Grand Trunk from bringing their train any closer. Afterward, the Grand Trunk workers tried to build another track along the north side of the spur, but withdrew before nightfall without finishing. A group of constables positioned themselves at the scene of the dispute overnight to ensure neither side tried anything under the cover of darkness.

Aftermath

There were fears that the Grand Trunk would continue their retaliation the following morning, but cooler heads prevailed and they resigned to legal methods from that point forward. A contingent of Grand Trunk and James Bay workmen spent that morning clearing the debris from the right-of-way. Unfortunately for both parties, the noise of the battle disturbed residents of nearby Rosedale; one of Toronto’s oldest, wealthiest and most influential neighbourhoods. While it would take another month for the dispute between the Grand Trunk and the James Bay Railway to go before the Board of Railway Commissioners, it only took a week for a compromise to be worked out between the two railway companies at the insistence of the city. Rather than carving their own path parallel to the Grand Trunk/Belt Line tracks along the west bank of the Don River, the James Bay Railway was to connect with it just southwest of the brickworks and use the existing tracks to enter Toronto.

By February 8th, each company had issued an injunction against the other. The ensuing legal battle lasted until the Grand Trunk Railway’s appeal was dismissed with costs two months later. It took until November 7th of that year for the companies to come to an agreement on the James Bay Railway’s use of old Union Station. They would have to pay the Grand Trunk one dollar for each baggage, mail, express coach and sleeping car entering Union Station, and another dollar for each such car departing Union Station (aka $2 per car in total, or approximately $55 per car when adjusted for inflation). By this point the James Bay Railway had officially rebranded as the Canadian Northern Ontario Railway, cementing itself as a local arm of the Canadian Northern system rather than a separate venture. Service between Parry Sound and Toronto finally commenced fourteen days later on November 19th. Since the trackage south of Rosedale continued to remain in the hands of the Grand Trunk, many Canadian Northern timetables show their system beginning at Rosedale instead of Union Station. After Rosedale Station burned down in 1917, timetables often show the Toronto end of their lines beginning at Todmorden Station instead.

Today, the former James Bay/Canadian Northern route through the Don Valley might be better known as GO Transit’s Richmond Hill Line or the CN Bala Subdivision. The sign for Rosedale siding just south of the DVP Bayview Avenue offramp is positioned at roughly the same place Rosedale Station was – marking the spot where the James Bay Railway connected with the Grand Trunk/Belt Line 119 years earlier. The location of the battle is a little bit harder to find – any evidence of the Grand Trunk spur to Todmorden Mills that could have survived after 1906 was erased when the Don Valley Parkway was built in the early 1960’s, rerouting the Don River and changing the surrounding landscape considerably.

Written by Adam Peltenburg

References

An Act to incorporate the Lake Nipissing and James Bay Railway Company. 1884. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_08051_13_2/138.

The Toronto World. 1885. “Opening of the Canadian all Rail Route to Winnipeg and the Rocky Mountains.” November 3, 1885. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_18851103/3.

Riff, Carl. 2013. The Northern Railway of Canada Diary. Hamilton, Ontario: n.p.

An Act to incorporate the James Bay Railway. 1895. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_08051_24_2/38.

“The James Bay Railway.” 1897. 17. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.07525/8?r=0&s=1.

The Toronto World. 1903. “Will Ask For Subsidy For James Bay Railway.” August 31, 1903.

The Toronto World. 1904. “Mackenzie-Mann Spring a Mine; Will Expropriate Burned Area.” July 5, 1904. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19040705/2.

The Toronto World. 1905. “Railway Commissioners Big Docket in Toronto.” November 8, 1905. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19051108/3.

The Semi-Weekly Colonist. 1905. “The Canadian Northern.” February 7, 1905. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00333_19050207/2.

The Toronto World. 1904. “Grand Trunk Now Returns To Its First Proposition.” September 14, 1904. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19040914/1.

“Can. Pac R. W. Co. v. Grand Trunk R. W. Co.” 1906. The Ontario Weekly Reporter 7, no. 19 (May). https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_06873_195/38.

The Toronto World. 1905. “Progress on James Bay Railway.” September 25, 1905. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19050925/5.

The Toronto World. 1906. “Railways in Don Valley Battle for Right of Way.” February 7, 1906. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19060207/1.

The Hamilton Evening Times. 1906. “Railways War In Don Valley.” The Hamilton Times (Hamilton), February 7, 1906. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00138_190601/309.

The London Advertiser. 1906. “Railways in the Don Valley Battle for Right-Of-Way.” February 7, 1906. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00255_190512/410.

The Semi-Weekly Colonist. 1906. “Rival Railroads Declare Peace.” February 9, 1906. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00333_19060209/1.

The Toronto World. 1906. “Trains Running in a Month.” March 9, 1906. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19060309/1.

The Toronto World. 1906. “Supreme Court Judgements.” April 7, 1906. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_19060407/14.

“Canadian Railway and Marine World.” 1915. In The Canadian Northern Railway’s Use of Toronto Union Station. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_06968_40/30.

Canadian National Railways Accounting Department, A. B. Hopper, and T. Kearney. 1962. “The Canadian Northern Ontario Railway Company.” Synoptical History of the Canadian National Railway Company, (October), 183-186. https://railwaypages.com/cnr-synoptic-history-to-1960.

The Star. 1906. “First Regular Train Over Canadian Northern.” November 20, 1906. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00371_19061120/7.