Not to be confused with the Canadian Northern Railway.

Introduction

The Northern Railway of Canada, originally established as the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway in 1850, was Toronto’s first railway and the first steam-powered railway in Canada West. It would become one of several local railway companies to form during Canada’s railway boom era, establishing a strong foothold in the region during the 35 years it operated. Originally intended as a ‘portage’ route to connect Lake Ontario with Lake Huron, it would go on to reach Lake Erie at its southern end and Lake Nipissing in the north at its greatest extent. It provided Torontonians with the most direct rail connection with Canadian Pacific’s transcontinental line across some of the most difficult terrain in the province, a feat no other railway would achieve until two decades later. Even though it would ultimately amalgamate with the Grand Trunk Railway in 1888, much of the Northern Railway system actively carries passenger and freight trains today.

The Toronto Passage

Toronto, originally established by European settlers as the Town of York in 1793, has historically existed at the base of a portage route between Lake Huron and Lake Ontario. It offered a convenient shortcut while traveling through the Great Lakes, as well as helping to avoid the danger presented by Niagara Falls. The portage route, known as the Toronto Carrying-Place Trail or the Toronto Passage, involved walking over 100 kilometers between the two bodies of water. One of the earliest attempts at speeding up travel over this route was the construction of Yonge Street by the Queen’s Rangers under Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe between 1795 and 1816. Its purpose was strategic in nature, allowing for overland troop transport to make use of the Great Lakes and the defensible port in the Town of York. While Yonge Street initially only went as far as Lake Simcoe, an extension to Georgian Bay on Lake Huron was completed in 1827. The first railroad in North America, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, was chartered in the United States the same year. Steam-powered railroads had existed for 25 years by this point in time but took longer to proliferate on the North American continent. The United States would ultimately outpace Canada in railway development during the following two decades, much to the ire of Canadian business interests. Local efforts in this regard would only begin to increase several years after the City of Toronto was incorporated in 1834. A noteworthy attempt during this period was the Toronto & Lake Huron Railroad, which was chartered on April 20th, 1836, but ultimately failed to materialize.

Frederick Capreol arrived in Canada for his second time in 1833, during which he permanently emigrated from England and settled in Toronto. He began operating an auction room in 1840 and became a pivotal promoter of railway development in the area. In 1848, he announced his intentions to build a railway to Lake Huron. It would be called the Toronto, Simcoe and Huron Railroad Union Company. Funding the construction of the railway would be difficult, so Capreol suggested a novel way of securing it. A provincial lottery with a prize pot worth $2 million, while certainly a unique way of funding at the time, was ultimately shot down in a subsequent referendum due to its outlandish nature.

Since railway development in Canada had fallen behind that of the United States and Britain, the government sought to financially incentivize the construction of railway lines within the colony. The Guarantee Act was passed by the Province of Canada in 1849, ensuring that interest on half of the railway’s bonds were eligible for a guarantee from the government once half of a given railway line was complete. Eligibility was also determined by the length of the railway, which had to be at least 120 kilometers (75 miles) long. Capreol partnered with Charles Berczy to take advantage of the interest guarantee, chartering the company in July of the same year. The City of Toronto not only invested heavily in the railway, but also provided the necessary land for a station and the right-of-way. However, before construction could begin the company was re-chartered in 1850 as the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Union Railroad. On October 15th, 1851, a sod-turning ceremony and gala celebration was held in Toronto on the south side of Front Street just west of Simcoe Street, the site of today’s Metro Convention Centre. Lifting the ceremonial silver spade was Lady Elgin, the wife of the Earl of Elgin, the governor-general of the Province of Canada. The sod was deposited in a decorated wheelbarrow and wheeled away by the mayor of Toronto. A young engineer named Sandford Fleming, who would later help build the new railway, preserved the sod for posterity. 20,000 citizens turned out to enjoy a parade that began in front of City Hall at Front and Jarvis Streets. That night the day’s festivities culminated in a grand ball at St. Lawrence Hall, where famed soprano Jenny Lind, the “Swedish Nightingale,” performed in a concert arranged by American promoter P.T. Barnum. In a controversial move, Capreol was fired from the company two days before the ceremony took place.

Before the first rails could be laid, however, another condition was added to the loan interest guarantee that would influence railway development in Canada for decades to come. The Board of Railway Commissioners, formed by the Province of Canada in 1851 to administer the guarantee, decided in 1852 to require all eligible railways to use 5-foot 6-inch “provincial” gauge. This differed from the 4-foot 8.5-inch “standard” gauge which had become popular in the United States. It’s believed that this decision was influenced by the St. Lawrence and Atlantic Railroad, which was already under construction using the provincial gauge at the behest of business interests in Portland, Maine. Since the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron would only interchange with other Canadian railroads, this would initially present less of an issue for them than it did for other railroads in the province. During the same year as the Board of Railway Commissioners’ decision, the OS&H hired Frederick Cumberland as its chief engineer. Cumberland was a London-born architect who had recently moved to Toronto, and he would be responsible for the railway’s construction until he returned to his architectural practice in 1854.

Due to a lack of local manufacturers in Canada at the time, the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron ordered their first locomotive from the Portland Locomotive Works and had it shipped across the border by boat. The engine was named Lady Elgin and was initially used to assist in construction of the railway upon its delivery in October 1852. The resulting transportation costs and customs duties were prohibitively expensive, prompting railway executives to search for alternatives. Luckily for them, local foundry owner James Good had recently readapted his factory at the intersection of Yonge and Queen Street for the construction of steam locomotives in anticipation of demand. That factory’s first locomotive, and the second on the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron roster, was completed on April 16th, 1853. It was named Toronto after city in which it was built. At a weight of 29 tons and measuring 26 feet in length without the tender, the engine was considered quite large compared to other locomotives of the time. The challenge was now to move the engine from James Good’s Toronto Locomotive Works at the present-day site of St. Michael’s Hospital to the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron at Front Street. No tracks were in place between the two points, so the engine would have to move through more creative means. The locomotive’s tender was moved separately by a horse-drawn float on April 19th, though the engine itself was much too heavy for this method to work. Instead, temporary track was laid relay-fashion in 100-foot intervals while the engine was pushed forward manually with pushbars. The move made use of Queen Street and York Street, covering approximately 1.4 kilometers. This laborious process took five days, during which the engine was viewed by countless onlookers. It was finally delivered to the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway on April 26th.

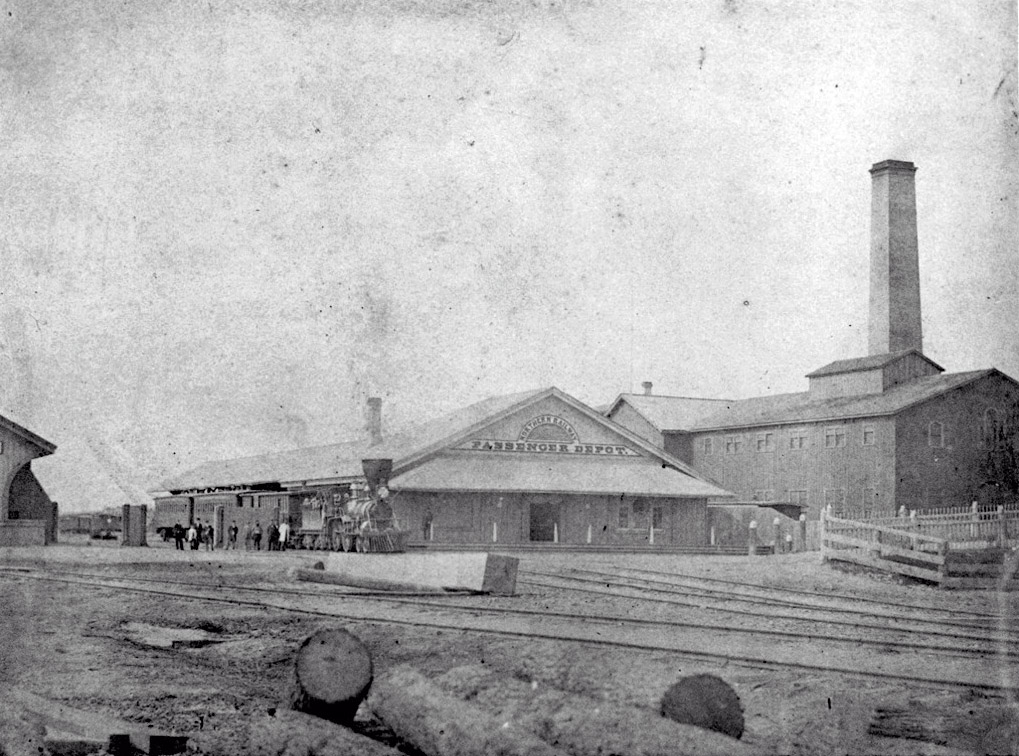

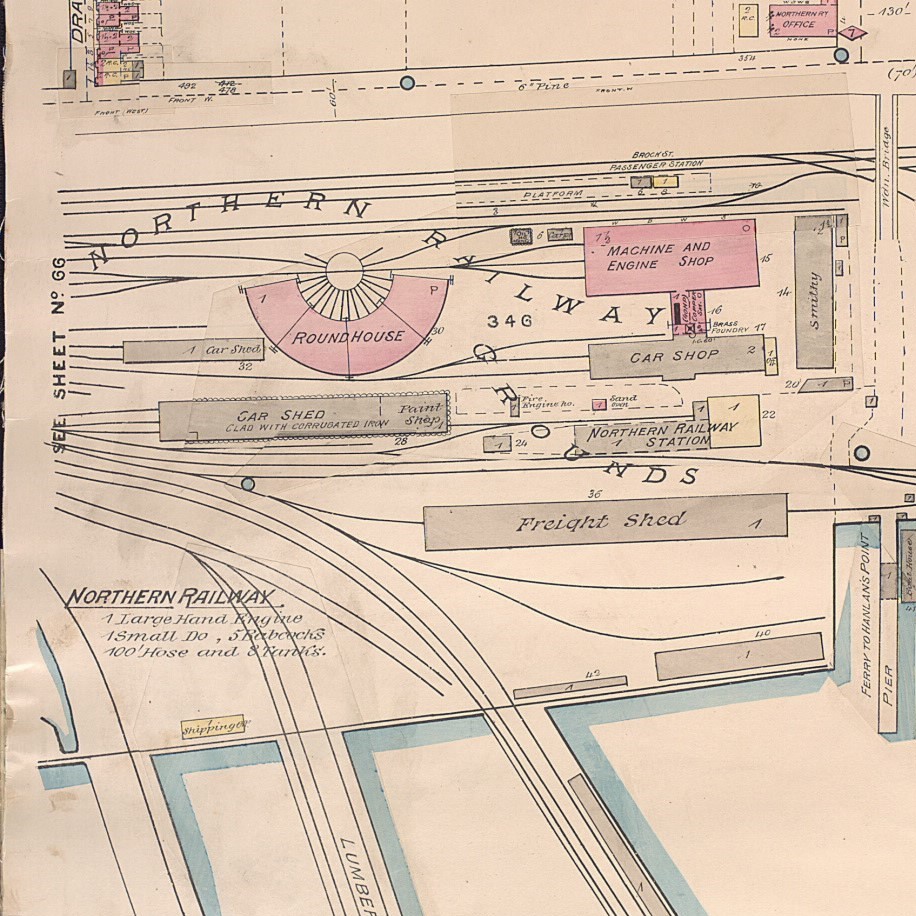

In Toronto, the railway would hug a narrow strip of land along the south side of Front Street from Fort York to Bay Street. At the latter location a crude wooden depot was built to serve as the railway’s primary passenger terminal for the city. On December 23rd, 1851, the railway had taken possession of all the land lying south of Front Street between Bathurst Street and Spadina Avenue for a freight terminal and maintenance facilities. At the eastern end of these lands an eight-stall roundhouse, machine shop, and car repair shop were built. A grain elevator was constructed on a new wharf just east of the older Queens Wharf. On May 16th, 1853, the first passenger train steamed out of Toronto for Machell’s Corners, now Aurora. The locomotive Toronto was used to pull two boxcars, a passenger coach and a combination coach and baggage car. The first freight consignment consisted of a chest of tea, a dozen brooms and a barrel of salt. For now, this is where the railway would end as work was still underway on the line beyond Aurora to Lake Huron. Having beaten the nearby Great Western Railway to revenue service by six months, this made the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway the first steam-powered railway in Canada West.

The Oats, Straw & Hay

Construction of the OS&H continued vigorously throughout the rest of 1853. In June of the same year, company directors selected a specific location on the shore of Lake Huron for the railway to terminate. A rural area west of the mouth of the Nottawasaga River – the modern-day site of Collingwood, Ontario – was their choice. In doing so, the railway’s right-of-way was shifted in a westerly fashion away from the soon-to-be Village of Barrie and through the comparably sized community of Allandale. The Ontario, Simcoe & Huron extended service to Bradford on June 13th, 1853, then to Allandale on October 11th of the same year. While work on the mainline was ongoing, a 2.3-kilometer branch line was opened between Lefroy and the shore of Lake Simcoe at Belle Ewart on May 2nd, 1854. The purpose of this line was twofold depending on the season – for lake-faring steamship passengers during the summer months, and for the shipment of lake ice for food preservation during winter. On December 16th, 1854, construction of the mainline to Collingwood was officially completed and, on that date, a special train carrying railway officials made the journey from Toronto in three hours. Regular service to Collingwood would not commence until three weeks later on January 2nd, 1855. The surrounding community, which was little more than a clearing in the woods known as Hen and Chickens Harbour, would be incorporated as the Town of Collingwood three years later. Here, the OS&H built what was then the grandest passenger station on their entire system. Its design was heavily influenced by Spanish architecture styles. A total of eight arched portals, three of which were occupied by tracks, were perhaps the building’s most striking features. The OS&H station in Toronto was little more than a wooden shed by comparison.

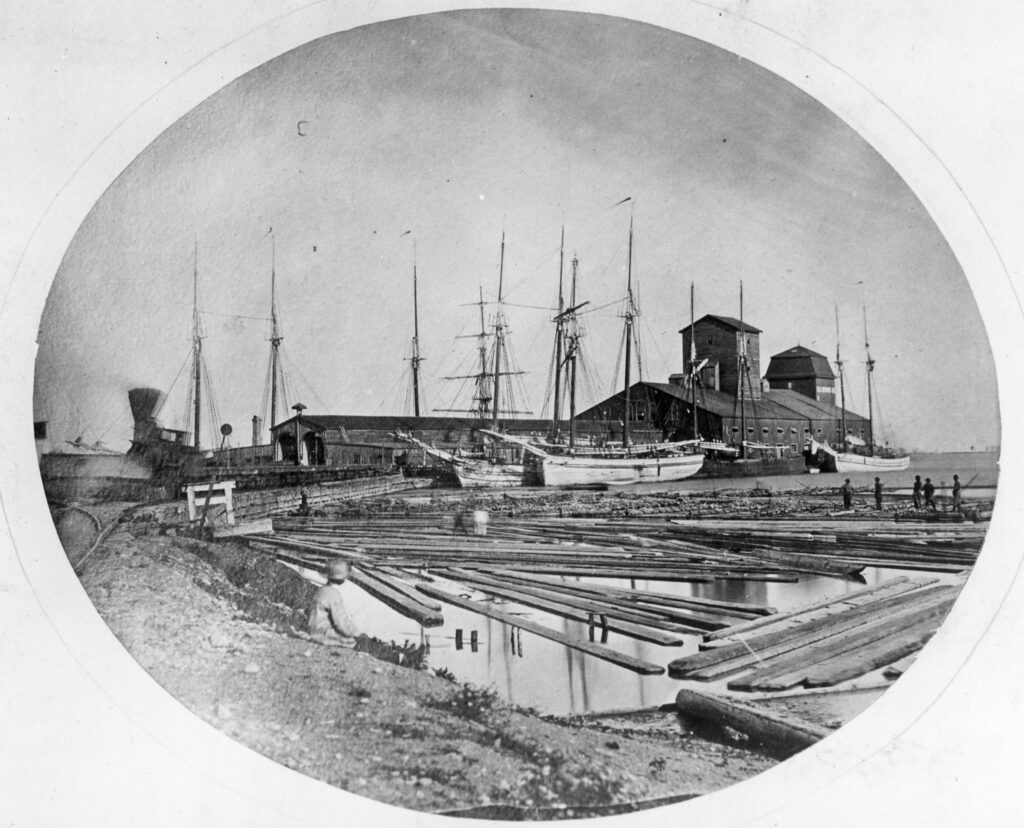

Above all, the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron quickly became known for its shipment of grain. So much so that it was even briefly nicknamed the “Oats, Straw & Hay” – a play on the OS&H acronym. The grain would move by ship from ports on the Great Lakes to the Collingwood Harbour, then by train to the railway’s wharf in Toronto from which it would be picked up by another ship and brought further east. When the St. Lawrence River or Lake Ontario froze over during the winter, it could be brought east by rail once the Grand Trunk Railway opened between Toronto and Montreal in 1856. The destination was often New York City as the transportation infrastructure at the time was such that this route was the cheapest. Wood was the other profitable commodity most often carried by the OS&H, which was also an important source of fuel for the railway itself. The primitive boilers of steam locomotives at the time could only burn cordwood, piles of which could often be found next to the tracks at frequent intervals for easy access. Wood destined for Britain was used for building material and ship masts. Lengths of squared timber over a hundred feet long were transported on special spar trains made up of a series of three flat cars attached together with long chains. These trains ran all night long so as not to interfere with regular traffic. The timber was then dumped into Toronto harbour and lashed together with saplings into giant rafts that were four or five layers in depth and up to a quarter mile in length. These rafts were then sailed across Lake Ontario and down the St. Lawrence River to Quebec City where the timber was loaded onto ships bound for England. The immense old growth forests along the OS&H right-of-way were originally so thick that passengers complained that they couldn’t see anything except trees from the windows of the coaches. Within a matter of decades, the opposite would be true thanks to the ease at which logging could be done in proximity to the railway.

In spite of the massive quantities of freight the railway was now moving, it struggled to turn a profit early on. A variety of factors were to blame including the economic effects of the Panic of 1857. A group of paddle steamships were chartered and later purchased to operate between Collingwood and Chicago, but their operating costs had quickly exceeded the income they produced. Frederick Cumberland rejoined the railway as a company director in 1857, becoming vice-president of the board a year later. When the railway declared bankruptcy during the same year, he was sent to England for negotiations over the company’s debts. Cumberland only did this on the condition that he would be made general manager of the company which was swiftly granted. From this point forward Cumberland would initiate efforts to vastly improve the railway’s profitability. It was reorganized in mid-1858 as the Northern Railway of Canada. The name was likely chosen due to the past tendency of Torontonians to simply refer to the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron as the Northern Railway in common parlance. Unprofitable freight moves and express passenger trains were subsequently cut, along with the steamships based out of Collingwood.

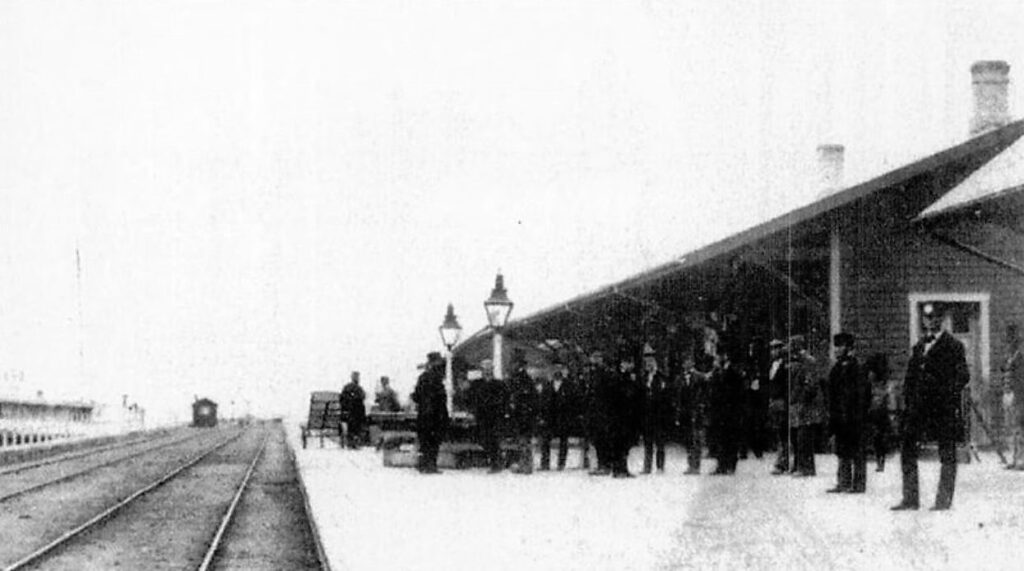

While the railway was certainly focusing more on savings, this period was also marked by some investment in new equipment and infrastructure. For the most part, this was done entirely out of necessity. On October 18th, 1857, less than a year before the Northern Railway’s reorganization, their original station at Bay Street in Toronto burned to the ground. While a new station was erected elsewhere the Northern Railway temporarily moved into Toronto’s newly built Union Station, which first opened on June 21st, 1858. A new permanent passenger station was built on the west side of Brock Street (now Spadina Avenue) and officially opened on January 9th, 1861. The station was nestled within the Northern Railway’s repair shops, directly between the car shop and a freight shed. New head offices for the railway were built in a Georgian-style building at the northeast corner of Spadina Avenue and Front Street in 1861. In addition to the earlier grain elevator located at the Collingwood Harbour, a second grain elevator was constructed south of the harbour in 1862.

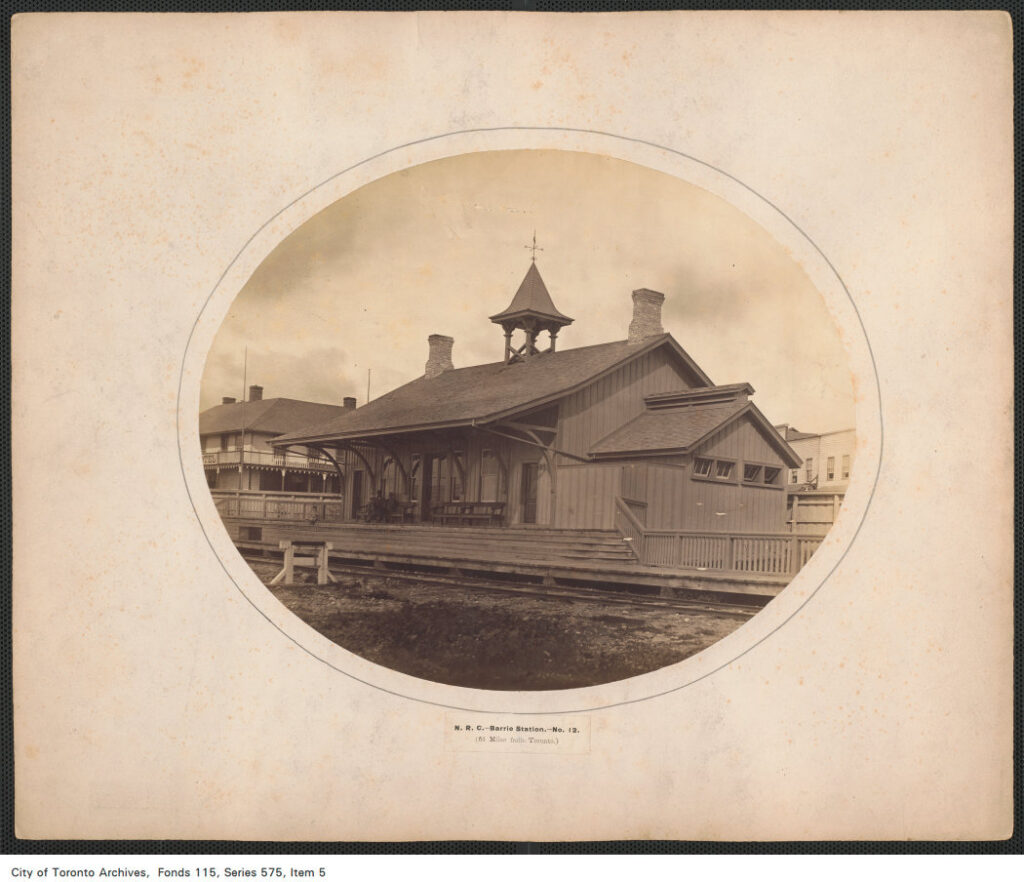

The only real expansion of the Northern rail network during this decade came as a result of a dispute with the village of Barrie almost dating back to the railway’s inception. The county had raised 50,000 pounds for construction of the railway, and it was the understanding of the local populace at the time that the railway would pass directly through Barrie. When it was discovered that the railway was rerouted towards Collingwood, a deputation from Barrie was sent to Toronto in January 1853 to negotiate with the directors of the company. The directors argued that to route their mainline through Barrie at this point would cost the railway an addition 10,000 pounds. As an alternative, the deputation claimed to have made a verbal agreement with the directors for the construction of a branch line from the Allandale Station to Barrie, along the shore of Kempenfelt Bay. The construction of this line would be done entirely at the cost of the railway except for the land it was to be built on, which would be given to the railway free of charge. A resolution was passed by the railway later the same month to build the branch, known as the “Barrie Switch”, and advertisements began appearing in newspapers for tenders to build the branch on May 28th, 1856. Despite this, no progress was made in its construction. A pamphlet published in 1862 titled “The Barrie Switch” charged that the railway had awarded a contract to one A. A. McGaffey and that the company was legally obligated to build the branch, but the Northern Railway claimed no such contract had been signed. They also argued that the company’s reorganization in 1858 made it no longer bound by its prior obligations, and that the railway didn’t have the funds to build the branch if it wanted to. After further delays the Northern Railway relented and it began work on the Barrie Switch. The branch was officially opened on June 21st, 1865, and to celebrate the occasion a special train departed Toronto for Barrie. The train was particularly heavy with 22 fully loaded passenger cars, requiring two locomotives to pull it. A grand celebration was held in Barrie which included numerous speeches from politicians and railway officials.

Reinvigorated Expansion

The Northern Railway’s resistance to expansion only lasted about a decade as its financial situation began to improve, as well as a variety of outside factors. As the Barrie Switch saga was occurring, local residents of the neighbouring counties of Grey and Bruce to the west were equally insistent that a railway was necessary to bring prosperity to their communities. Their focus was naturally turned to the Northern Railway, whose terminus in Collingwood was only a few kilometres east of the borders of Grey County. The additional grain elevator which the railway had built there in 1862 was intended to serve the farmers of Grey County, but for many of them the distance was still very inconvenient. On April 25th, 1866, Barrie’s Northern Advance newspaper made note of other outlets in those counties expressing that discontent. Included in the article was the full text of a letter written to the Northern Railway’s executives by A. Shaw, Esq., a lawyer from Walkerton. The following excerpt summarizes Shaw’s position:

“With respect to the railways, my great desire is to see them extended into the division as soon as possible. Until Grey and Bruce possess railway facilities they will labour under great disadvantages as compared with counties nearer markets and traversed by railroads. Just consider what would have been gained by these two counties, had they been able to send all their products to market during the period of high prices that prevailed last autumn. The proceeds they would have received then, in excess of what they probably will receive, would built [sic] many miles of railway”.

After speaking with executives of the Northern Railway, Shaw noted that while plans to expand west existed they were not to his satisfaction. At the time, the railway was concerned with keeping out competition and the plans which existed at that time would involve a branch line splitting off from the mainline no further north than Bradford. Whether such plans were treated with any seriousness by the railway, they would not be acted upon until well after the Northern Railway had competition at its doorstep. The Toronto, Grey & Bruce Railway was incorporated on March 4th, 1868, promising to reach numerous communities the Northern Railway had neglected as well as ending its monopoly on firewood, among other things. By 1871 it had already reached Bolton while pushing towards Owen Sound. On February 15th of that year, the Northern Railway finally sprang to action. The North Grey Railway was chartered to construct a railway line from Collingwood to Meaford with authority to extend further west to Owen Sound. At the time, Meaford was a burgeoning community located about 35 kilometres up the shore of Georgian Bay and firmly within Grey County. As would be the case with all future expansions of the Northern Railway from this point forward, the North Grey Railway would exist solely on paper and was simply an extension of the Northern Railway. Work on the North Grey Railway pressed on “with energy” through 1871 according to a company report from the Northern Railway. A contract for construction of Meaford Station at the end of the line was awarded to a Mr. F. Law on July 1st, 1872, and was completed before the end of the year. Measuring 300 feet in length, the wooden structure was large enough to contain both passenger and local freight facilities. It was perched atop the aptly named Station Hill at the south edge of town. The railway was finally opened to Meaford on November 20th, 1872, though an extension to Owen Sound was never pursued. This was likely due to the Toronto, Grey & Bruce Railway reaching it the following year, combined with the steep grades that the railway would have to climb west of Meaford.

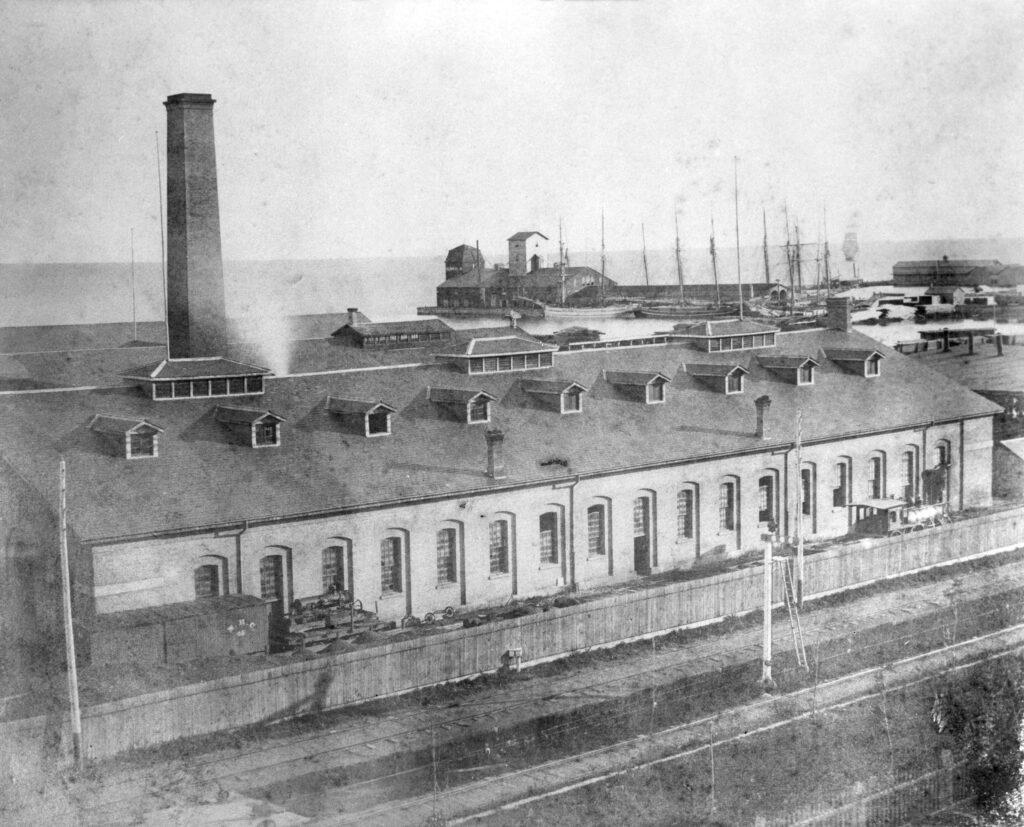

During the same period, the Northern Railway made numerous improvements to its facilities in Toronto. On June 10th, 1867, a new passenger station was built on the east side of downtown Toronto at the corner of The Esplanade and Market Street. The City Hall Station, as it was known, was mostly built as a convenience for farmers who wished to bring their products to the market square near Front Street and Jarvis. In attendance at the new station’s opening ceremony was none other than John A. Macdonald, who would become the first Prime Minister of the Dominion of Canada three weeks later. In 1870, the Northern Railway’s earlier grain elevator at the harbour west of Spadina Avenue burned down, prompting the railway to build a new one measuring 140 feet in height and capable of storing up to 260,000 bushels of grain. When the Northern Advance newspaper in Barrie reported on the experience of riding the Northern Railway from Toronto on October 9th, 1871, it described the new grain elevator as the “first object of interest” when departing the city and observed that it “rose over ever surrounding object”. A new roundhouse had also been built on the west side of Spadina during the same year, replacing an older eight-stall enginehouse which was made from wood and dated back to the railway’s beginnings. The new structure was predominantly made from brick, had a total of fourteen locomotive stalls, and according to the Northern Advance included a “fluted galvanized iron roof, ends, and sides, and doors sheathed with the same material”.

The Transcontinental Connection

“No railway in Canada has yet been constructed through a region so remote, and, at present, so inaccessible; no municipalities can be expected to aid it by bonuses, and the country through which it runs is too new to promise an early return of remunerative traffic.”

J. D. Edgar, President of the Ontario & Pacific Junction Railway, in a letter to W. H. Howland, President of the Toronto Board of Trade

December 17, 1875.

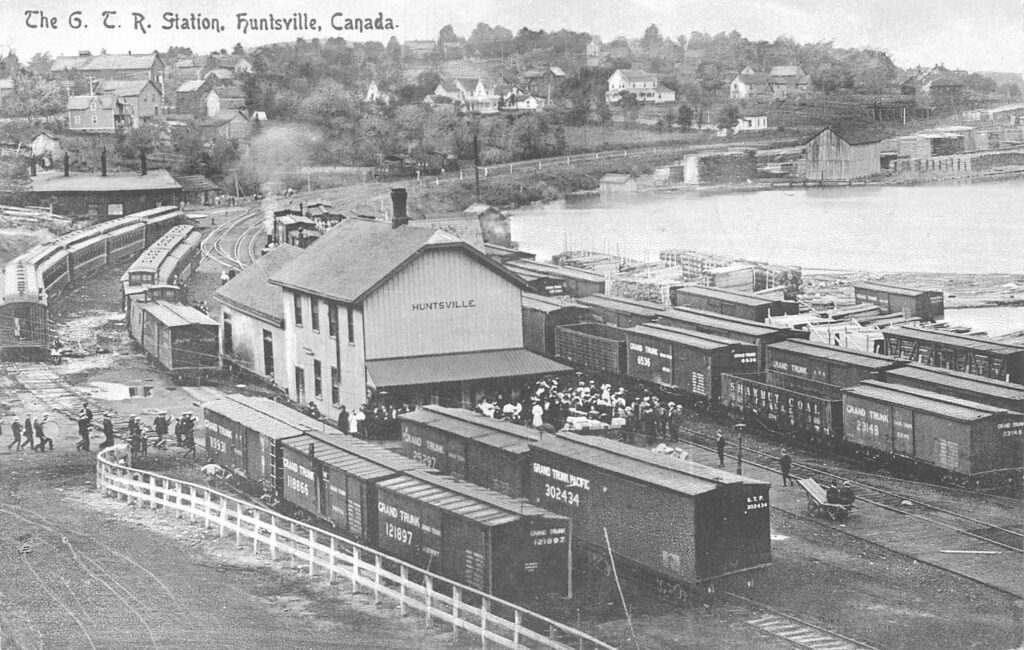

Multiple economic forces were pushing the railway much further north, the logging industry in particular as sources of lumber in the immediate vicinity of the Northern Railway mainline were exhausted. To this end, the Toronto, Simcoe & Muskoka Junction Railway was incorporated on December 24th, 1869, with the purpose of building a railway to the southern tip of Lake Muskoka. It would begin where the Barrie Switch ended near downtown Barrie, pushing northeast along the northerly shore of Kempenfelt Bay and Lake Simcoe to Orillia before crossing the Atherley Narrows. From there, it would continue north up the east side of Lake Couchiching to Washago before entering what was then the Free Grant Land District of Muskoka. On December 10th, 1870, the contract for construction of the railway to the Severn River was awarded to Ginty & Co. The first train arrived in Orillia just under one year later on November 15th, 1871, although regular service would not commence until November 30th. Construction beyond that point to Gravenhurst took much longer despite the distance being almost the same. The railway reached Washago in 1873, crossed the Severn River in 1874 and made it to Gravenhurst by late 1875. The railway opened its Muskoka Wharf just west of Gravenhurst the following year, providing a direct connection to steamship traffic on Lake Muskoka in much the same way it did to Lake Simcoe two decades earlier. For much the same reasons behind the Toronto, Simcoe & Muskoka Junction Railway, the North Simcoe Railway was chartered on March 24th, 1874 as a means to reach the near-untapped logging potential in the northern reaches of Simcoe County. Its planned route was originally to go only between Barrie and Penetanguishene on the shore of Georgian Bay. However, the charter was quickly amended later the same year as a means to compete with the upstart Hamilton and North-Western Railway, which was rapidly pushing into the Northern Railway’s territory. It would have the power to extend south to either the Northern Railway in King City or the Toronto, Grey & Bruce Railway in Bolton. However, only a much smaller segment would be built from Colwell to Penetanguishene and the first regular train service began in February of 1879.

However, there was something of arguably greater importance that incentivized the railway to push even further into the rugged Canadian Shield. On July 1st, 1867, the British North America Act united the British colonies of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and the Province of Canada into the Dominion of Canada. In 1870, the colony of British Columbia sent its stipulations for joining Canada, one of which was the construction of a transcontinental railway to connect it with the rest of the country. The contract for its construction was won by Sir Hugh Allan, a Scottish-Canadian entrepreneur responsible for a variety of other successful business ventures in North America. The Canadian Pacific Railway – a company unaffiliated with the railway of the same name that exists today – was chartered on June 14th, 1872, and Hugh Allan was appointed president of the company five days later. The transcontinental railway was intended to start at a point somewhere near Lake Nipissing, an area which was still many kilometres away from the nearest railway development.

It was self evident that any railway company that could reach that point and connect with the transcontinental railway would benefit massively from through traffic to or from the west. Railways approaching it from the east through the Ottawa River valley were at an advantage terrain-wise, as well as having financial backing from business interests in what was then Canada’s largest city and economic engine – Montreal. Numerous branch lines in the vicinity of Toronto immediately became interested in doing the same, though the engineering challenges and costs of venturing into the terrain north of Lake Simcoe was prohibitive to say the least. Despite these challenges, the Northern Railway’s general manager Frederick Cumberland was very interested in this opportunity, so much so that he was even named a company director in the original Canadian Pacific Railway’s charter.

His plans for a connection with the transcontinental went through numerous changes and revisions over the course of the next two decades. The very first iteration – called the Sault Ste. Marie Railway and Bridge Company – was incorporated on April 14th, 1871, over a year before the transcontinental railway even received its charter. Its stated purpose was to build a railway connecting the village of Sault Ste. Marie with the transcontinental railway at a point near Lake Nipissing, the exact location of which was omitted as the precise route of the Canadian Pacific Railway in that area had not yet been chosen. Even though Frederick Cumberland was also directly involved in this scheme, the addition of a “branch line” to connect with his Northern Railway at Gravenhurst was comparatively worded as though it would be secondary in nature. No significant progress could be made before the railway encountered its first major roadblock. On April 2nd, 1873, Liberal Party politician Lucius Seth Huntington exposed a large donation made by Sir Hugh Allan to Prime Minister John A. Macdonald to secure his contract for the transcontinental railway. The so-called Pacific Scandal led to Macdonald’s resignation on November 5th of that year and the end of Sir Hugh Allan’s Canadian Pacific Railway.

Despite the effect the scandal caused throughout Canada’s railway industry, the Northern Railway’s efforts to push north re-emerged soon thereafter with the incorporation of the Ontario & Pacific Junction Railway on May 26th, 1874. Once again, the plan associated with it originally had very little to do with Toronto. Its main line was to extend from Georgian Bay at the mouth of the French River to the southeast shore of Lake Nipissing with powers to extend south and east. However, it was quickly changed to focus on a direct connection between the now-uncertain transcontinental railway and Toronto. A resolution moved by James Gooderham Worts at a Toronto Board of Trade meeting on July 3rd, 1874, and subsequently quoted in a letter to the president of the Ontario & Pacific Junction Railway on December 17th, 1875, outlined the concerns of the business community in Toronto at the time:

“That it is of immense importance to the commercial interests of the Province of Ontario, and to Toronto in particular, that the earliest communication should be had by a railway between the proposed eastern terminus of the Canada Pacific Railway [sic] and the railway system of Ontario”.

Something of particular interest in the Ontario & Pacific Junction Railway’s charter was the requirement for it to be built to 4-foot 8.5-inch standard gauge, contrasting with the 5-foot 6-inch gauge of the rest of the Northern Railway system. The federal government had removed the gauge condition on its loan interest guarantee in 1870 and adopting the standard gauge was even considered for the Toronto, Simcoe & Muskoka Junction Railway back in 1871. By this point in time, it had become clear that the broad gauge had too many drawbacks, particularly as it related to interchanging with the standard gauge railroads of the United States. Since the Grand Trunk Railway and Great Western Railway had already made their conversions to standard gauge in the early 1870’s the disparity was slowing down interchange between these railways and the Northern Railway. It was able to obtain legislation allowing it to convert its gauge to standard in 1876, though the costs associated such a conversion would delay progress on that front for several years.

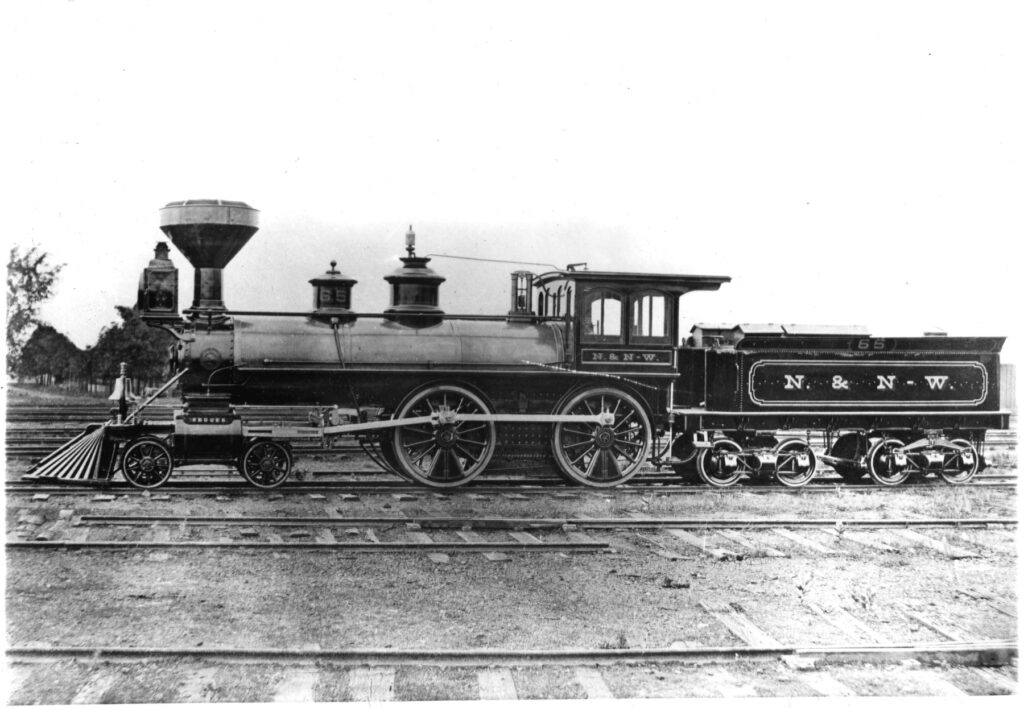

The Northern and North Western Railway

From its formation in 1872 and through the rest of the decade, the Hamilton & North-Western Railway had been steadfast in encroaching on the Northern Railway’s territory in Simcoe County. What was shaping up to be a fierce rivalry between the two companies quickly took a different turn when the two decided it would be favourable for both parties to combine their operations. On June 10th, 1879, an agreement between the Northern Railway of Canada and the Hamilton and North-Western Railway to consolidate their operations under a single management was ratified by both companies at their respective meetings. The agreement took effect on July 1st, 1879, after which a joint executive committee made up of four representatives from the boards of each company took office. The managing director of the Northern Railway – Frederick Cumberland – would serve as chairman of the executive committee. Work began immediately to effectively operate the two entities as one, including the re-gauging of the Northern Railway system. Parts of it were re-gauged in sections over the following two years. The Northern Railway’s broad-gauge equipment was then subsequently converted to standard gauge or disposed of. In a remarkable feat of engineering prowess, the entire Northern Railway mainline from Toronto to Gravenhurst was converted to standard gauge in a single day on July 9th, 1881. The remainder of the broad gauge was converted over the next five days, making the Northern Railway the last broad-gauge railway in Ontario to convert to standard.

The combined system, which was managed under the combined name of the Northern & North Western Railway from that point forward, now stretched from Port Dover on the north shore of Lake Erie to Gravenhurst. Despite the numerous differing interests of the board members, the combined capital of both companies could help fund their mutual goal of a connection with the transcontinental railway. After John A. Macdonald won the 1878 federal election, efforts to build the Canadian Pacific Railway picked up in stride. A map was drawn up in 1880 showing the planned route of the Ontario & Pacific Junction Railway with two alternative connections with the Canadian Pacific, depending on which side of Lake Nipissing it would go. The line from Lake Nipissing to Sault Ste. Marie was dropped due to the Canadian Pacific Railway planning to do the same. A 36-mile branch from about Skeleton Lake to Parry Sound was included but this was later dropped as well. The Canadian Pacific Railway Company, now led by a new syndicate unassociated with Sir Hugh Allan, was officially incorporated on February 16th, 1881. At about the same time, the Northern Railway’s plans for its connection with the transcontinental railway was changed to a certain extent. On March 21st, 1881, the Northern, North-Western and Sault Ste. Marie Railway was incorporated by individuals associated with the Northern Railway and with virtually the same route as the Ontario & Pacific Junction Railway. The new company became the Northern Railway’s primary vehicle for its transcontinental connection while the Ontario & Pacific Junction Railway had its route changed over the years, eventually fading into obscurity altogether.

The Northern, North-Western and Sault Ste. Marie Railway’s name was changed to the more concise Northern and Pacific Junction Railway on May 25th, 1883. On June 11th, 1884, tenders were finally opened for its construction. Work began shortly thereafter from the southern end of the line at Gravenhurst and the northern end at Nipissing Junction simultaneously, and by March 13th, 1885, the Toronto World triumphantly reported that the first segment of the Northern & Pacific Junction Railway had been completed to a point just south of the Muskoka River in Bracebridge. Between that point and Nipissing Junction is where some of the heaviest work occurred, involving rock cuts as deep as 50 feet and removing as much as 100,000 yards of stone and soil in places. The longest bridge on the entire line was a 3,900-foot wooden trestle near Powassan which required over a million feet of timber in its construction. On the morning of January 20th, 1886, the tracks of the northern and southern sections of the Northern and Pacific Junction Railway were joined together. There was still much work to be done before the line was ready for train traffic, but the joining of these segments shortened the distance by rail between Toronto and Port Moody, British Columbia by 342 kilometres (213 miles). Seven days later, a special train brought politicians, railway executives and contractors from Hamilton to inspect the recently completed Northern and Pacific Junction Railway. The train arrived in Gravenhurst at 2:15 that afternoon and stopped for the night in Burk’s Falls before continuing north at 7:15 the following morning. The train finally reached La Vase (later renamed Nipissing Junction), after which telegrams were sent to Prime Minister John A. Macdonald and Canadian Pacific Railway president Sir George Stephen to announce the train’s arrival.

More inspections were done over the following months as the passenger stations were built and the final touches were made. Regular passenger service commenced between Toronto and Sundridge on June 25th, 1886, though the remainder of the line to Nipissing Junction required further inspections. The final inspection to the junction with the Canadian Pacific Railway was done on August 5th of that year, after which it was opened for traffic. This was just over a month after Canadian Pacific had begun transcontinental train traffic between Toronto, Montreal, and Port Moody on June 28th.

The Swift End of the Northern Railway

The death of Frederick Cumberland on August 5th, 1881 was felt throughout the Northern and North Western Railway and the companies it managed. The N&NW joint executive committee report for the year 1881 opened with an acknowledgement of Cumberland’s death, noting that it “occurred at a peculiarly unfortunate moment, and undoubtedly, in some degree, injuriously affected the result of the year’s working”. Suspicion and clashing interests between the Hamilton & North-Western and the Northern Railway executives would only be exacerbated by this event, and the ever-encroaching influence of the Grand Trunk Railway would further stretch the divide. While the Northern and Pacific Junction railway was being constructed, the larger Grand Trunk had been slowly gaining influence over its parent companies. An editorial from the Hamilton Spectator on May 1st, 1883 reported that a municipal council member had directly accused the Northern and North Western’s new general manager Sam Barker of being controlled by the Grand Trunk Railway and its general manager, Joseph Hickson. The Grand Trunk was actively trying to gain control of as many smaller railways as it could before the Canadian Pacific Railway encroached on their territory. It had used similar tactics to acquire the Great Western Railway in 1882, followed shortly after by the Midland Railway of Canada in 1884. Through the 1880’s the Grand Trunk had been gradually buying up shares in the Northern Railway and the Hamilton & North-Western Railway, and by 1887 it had gained a controlling interest. On January 24th, 1888, the entire Northern & North Western system was merged into the Grand Trunk Railway by deed of union, marking the end of the Northern Railway as a corporate entity.

While it ceased to exist, many pieces of the Northern Railway’s legacy persisted into the present day. An original passenger station which had been built by the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron in 1853 on the original stretch between Toronto and Aurora was preserved and restored at the King Township Museum in King City. Although slightly modified by the Grand Trunk Railway at a later date, it represents the only survivor of the early OS&H stations and is considered to be the oldest surviving railway station in Canada. Other surviving stations which can be traced back to the Northern Railway’s subsidiaries can be found in Craigleith on the former North Grey Railway and in South River on the Northern and Pacific Junction Railway. The Northern Railway’s repair shops on the west side of Spadina Avenue in Toronto, parts of which dated back to the 1860’s or earlier, continued to find use under the Grand Trunk Railway and Canadian National until their maintenance facilities in Toronto were consolidated at the nearby Spadina Roundhouse in 1927. The railway’s 100th anniversary in 1953 produced much fanfare, and festivities included a special train of vintage equipment over the original OS&H mainline. A plaque commemorating the 100th anniversary of the first train of the OS&H Railway was placed on a column of Union Station during the same year, though it disappeared during renovations in the 1990’s and has yet to be found. Thousands of commuters who make use of GO Transit’s Barrie Line continue to pass over a right-of-way established over 170 years prior by the OS&H Railway. Freight operations also continue over the former Northern and Pacific Junction Railway north of Washago, and a small stretch of the OS&H line west of Barrie continues to see service by the Barrie Collingwood Railway. In 2023, a ceremonial parade staff from the sod-turning ceremony of the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway in 1851 was generously donated to the Toronto Railway Museum.

Written by Adam Peltenburg

References

Boles, Derek. 2009. Toronto’s Railway Heritage. N.p.: Arcadia Publishing.

Cooper, Charles. 2014. “Northern Railway of Canada Group.” Charles Cooper’s Railway Pages. https://railwaypages.com/northern-railway-of-canada-group.

Cooper, Charles. 2014. “Railway Gauges in Ontario.” Charles Cooper’s Railway Pages. https://railwaypages.com/railway-gauges-in-ontario.

Brown, Robert R. 1952. “Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway.” The Railway and Locomotive Historical Society Bulletin, no. 85 (March). http://www.jstor.org/stable/43520050.

Hunter, Andrew F. 1909. A History of Simcoe County. Vol. 1. Barrie, Ontario: Barrie County Council. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.76847/84.

Riff, Carl. 2013. The Northern Railway of Canada Diary. Hamilton, Ontario: n.p.

Barrie Examiner. 2016. “LOCAL HISTORY: Boom and bustle in Belle Ewart.” Simcoe.com. https://www.simcoe.com/living-story/8428886-local-history-boom-and-bustle-in-belle-ewart/.

An Act to amend the Act intituled, An Act to incorporate the Toronto, Simcoe and Lake Huron Union Rail-road Company. 1850. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.47123/49.

The Breaking Ground. 1851. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.47123/73.

The Queen’s Wharf Depot Lands, Appointment of Committee of Enquiry. 1872. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.25157/9.

“The First Locomotives in Ontario.” 1902. The Railway and Shipping World, no. 56 (October). https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_04818_56/6.

Lavallée, Omer. 1959. The Railway Stations of Toronto. https://bzglfiles.s3.ca-central-1.amazonaws.com/u/131959/384c0324aa91e7cd4a63373ddc69a3a5e34af820/original/3c-torontos-early-and-union-stations-crha-1959-omer-lavall-e.pdf?response-content-type=application%2Fpdf&X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Crede.

The Toronto Sunday World. 1914. “Sixty Years of Railway Development in Toronto.” May 17, 1914. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00717_19140517/1.

The Barrie Switch, A Brief Statement of a Matter of Dispute Between the Corporation of the Town of Barrie and the Northern Railway Company of Canada. 1862. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.50491/10.

Taylor, James P. 1899. The Cardinal Facts of Canadian History. N.p.: The Hunter, Rose Co., Limited. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.24659/157.

An Act to amend the Acts relating to the Ontario, Simcoe and Huron Railroad Union Company. 1858. Toronto, Ontario: John Lovell. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_07713/2.

Northern Railway of Canada. 1862. “The Barrie Switch: Reply By The Directors.” 36. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.50419/7.

The Northern Advance. 1866. “The Railway Question in Grey and Bruce.” April 25, 1866.

The Northern Advance. 1871. “A Trip Over the Northern Railway.” October 9, 1871.

Northern Railway of Canada. 1872. Report for Year 1871, Report submitted by the Board of Directors of the Northern Railway of Canada, to the annual meeting of the proprietors. Toronto, Ontario: Globe Printing Company. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_00576_12/9.

A Consolidation of the statutes relating to the Northern Railway Company of Canada. 1876. Toronto, Ontario: Hunter, Rose & Co. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.33659/27.

Northern Railway of Canada. 1880. “Report for year 1879.” In Report submitted by the Board of Directors of the Northern Railway of Canada, to the annual meeting of the proprietors. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_00576_17/8.

Deed for Effecting the Union of the Grand Trunk Railway Company of Canada with the Northern Railway Company of Canada and the Hamilton and North Western Railway Company of Canada. 1888. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.06586/6.

An Act to Incorporate the Sault Ste. Marie Railway and Bridge Company. 1871. Ottawa, Ontario: I. B. Taylor. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_08050_4/164.

An Act to Incorporate the Ontario and Pacific Junction Railway. 1874. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_08051_3/398.

Ontario and Pacific Junction Railway Company. 1875. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.11521/6.

Statute Relating to the Northern, North-Western and Sault Ste. Marie Railway. 1881. https://books.google.ca/books?id=hqwNAAAAQAAJ&lpg=PA528&pg=PA161#v=onepage&q&f=false.

An Act to amend the Act to incorporate the Northern, North-Western and Sault Ste. Marie Railway. 1883. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015074701312&view=1up&seq=680.

An Act to Amend the Act to Incorporate the Ontario Pacific Railway Company. 1883. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015074701312&view=1up&seq=679.

The Toronto World. 1884. “The Ontario & Pacific Junction.” February 1, 1884. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_18840201/1.

The Toronto World. 1885. “Completed to Bracebridge.” March 13, 1885. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00367_18850313/1.

The Weekly Sun. 1886. “Canadian News.” January 20, 1886. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00373_18860120/3.

The Weekly Sun. 1886. “Arrival of the C.P.R. Train for the Pacific.” July 7, 1886. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00373_18860707/3.

Weekly Monitor. 1886. “General News.” June 30, 1886. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.N_00693_18860630/3.